Posted by jstevrtc on August 6th, 2010

The NCAA unleashed the database for academic progress ratings (APRs) for coaches in six different sports on Thursday. While it’s fun to plug in coaches from a few other sports — anyone surprised by Pete Carroll’s 971, 24 points higher than the college football average in 2008-09, and six-for-six over 925? — the most fun for us comes from plugging in the names of college basketball coaches and seeing how they did each year.

First, though, just a little background. The NCAA uses this little metric to determine how a team’s athletes are moving toward the ultimate goal of graduating, and the formula they employ to come up with the number is pretty simple. Each semester, every athlete gets a point for being academically eligible, and another for sticking with the school. You add those up for your team, then divide by the number of points possible. For some reason, they decided to multiply those numbers by 1,000 to get rid of the resulting decimal point (otherwise, it would have been as confusing as, say, a batting average), so if you get a score of .970, that means you got 97% of the points possible, and your APR score is 970. If you fall below the NCAA’s mandated level of 925, you get a warning, and then penalties if you don’t improve. Keep in mind, though, that if a coach changes schools, he shares his APR with the coach he replaced. And, the database only goes through 2008-09 right now. That’s why if you search for John Calipari, you’ll notice he has two APRs — a 980 that he received at Memphis which he shares with Josh Pastner, and a 922 for the same season at Kentucky which he shares with Billy Gillispie even though Calipari technically didn’t coach a game at Kentucky during that season. Because he was hired in 2009, he shares the APR with the preceding coach. You get the picture.

Why is this man smiling? How about two straight perfect APRs?

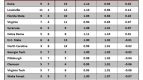

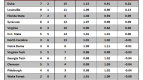

A couple of the numbers that people have been talking about the most since the database was released are the two perfect 1,000s put up by Bob Huggins‘ last two West Virginia teams. Most college basketball fans like to point the dirty end of the stick at Huggins when it comes to academics, and he’s been a lightning rod since his days at Cincinnati; rightly so, since his last three years as Bearcat boss saw APRs of 917, 826, and a eyebrow-raising 782. But his scores in Morgantown have been excellent, so he’d appreciate it if we all found a new poster boy for academic underachievement.

An AP report today specifically mentioned Connecticut’s Jim Calhoun, who, in the six years the database covers, has had teams better than the national average — and over the 925 cutoff — only three times. In fact, the APRs of his last three teams have steadily declined, posting scores of 981, 909, and (ouch) 844 from 2006-2009. The same AP report fingered Kelvin Sampson as having even more harrowing results, having only two years in which he topped 900 (his 2004-05 Oklahoma squad scored exactly 900) — his 2003-04 Oklahoma team posted a 917, and his final roster at Indiana in 2007-08 turned in a downright hurtful 811.

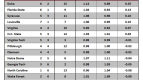

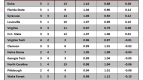

With a new toy like this, there was no way we could keep from checking all of the APRs of the Ivy League schools. The most impressive tally was by Columbia’s Joe Jones, who posted six straight perfect scores of 1,000 but will now evidently become an assistant on fellow Ivy man Steve Donahue’s Boston College team next season. Only two teams in the league didn’t score a perfect score for the 2008-09 season. The two bad boys of the league were Glen Miller, whose Penn team from that season put up — gasp! — a 950 (he had two straight perfect scores before that), and Tommy Amaker’s Harvard squad from that year, which posted a 985.

| player eligibility

| Tagged: apr, billy gillispie, bob huggins, boston college, cincinnati, columbia, connecticut, glen miller, harvard, indiana, ivy league, jim calhoun, joe jones, john calipari, josh pastner, kelvin sampson, kentucky, memphis, oklahoma, pennsylvania, pete carroll, steve donahue, tommy amaker, west virginia

Share this story