Past Imperfect: Kentucky-Louisville & the Dream Game

Posted by JWeill on March 28th, 2012Past Imperfect is a series focusing on the history of the game. Every two weeks, RTC contributor Joshua Lars Weill (@AgonicaBoss|Email) highlights some piece of historical arcana that may (or may not) be relevant to today’s college basketball landscape. This week: the original Dream Game between Louisville and Kentucky.

It was bound to happen someday. Despite Kentucky’s clear antipathy toward playing in-state archrival Louisville, there was going to come a time when it was simply unavoidable. That time finally came, was forced to come actually, on March 26, 1983, in Knoxville, Tennessee, in the Mideast Regional final, with a trip to the Final Four on the line.

No knowing observer was unaware of the possibility of a Bluegrass clash when the brackets were unveiled. Just a year prior, a similar tournament setup had been quashed when Kentucky was upset by Middle Tennessee State. This time around, the Wildcats got through, finishing off Bobby Knight’s Indiana squad, while Louisville was the one in trouble. After trailing significantly, the Cardinals edged Arkansas – coached by fairly-soon-to-be Kentucky coach Eddie Sutton — on a last-second tip-in. With both teams locked in to face each other, the pregame hype and buildup began.

Media outlets immediately began to call the matchup “The Dream Game” or even, more simply, “The Game.” The players did their best to try and avoid providing any potential bulletin board material, but to limited effect. Wildcats backup forward Bret Bearup acknowledged the “thing that must not be said:” “Anybody on either side who says he hasn’t been thinking about this matchup since the tournament started is just saying what he’s supposed to say so he won’t get in trouble. I say what I’m not supposed to. I’ve been dreaming about this game. This is great stuff. ‘Course now I’m in big trouble.”

But while Louisville entered the game ranked No. 2 to Kentucky’s No. 12, at least one major participant felt that it was the mighty Kentucky program that had more to lose.

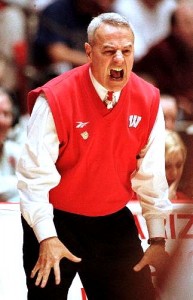

“The pressure is on Kentucky,” Louisville coach Denny Crum said in advance of the game, before needling the Big Blue Nation a little bit. “Our record is better the last 10 years. They have a chance to carve into our success.”

By tip-off, all the pregame discussions now past, everyone was ready. Tickets were at a premium and 12,489 showed up at the University of Tennessee’s Stokely Athletics Center for the game. Always eager to join a spectacle, Kentucky governor John Y. Brown wore a unique half-red, half-blue blazer to the affair.

Once the game finally got underway, it was Kentucky that broke quickly from the gate. Led by deft outside shooting by Jim Master and Derrick Hord, who each hit three early shots, the Wildcats raced to an early advantage, reaching a 23-10 lead just 10 minutes into the game. Louisville was playing tight, missing 16 of its first 20 shots.Crum’s roster was stacked, though, and the Cardinals’ talent began to show itself at last. Brothers Rodney and Scooter McCray found space underneath the basket and between them scored 12 of Louisville’s next 16 points. When Charles Jones hit a lay-up just before halftime, the UK lead was down to just seven, 37-30.