Past Imperfect: The Best Temple Team There Ever Was

Posted by JWeill on February 25th, 2011Past Imperfect is a series focusing on the history of the game. Every Thursday, RTC contributor JL Weill (@AgonicaBoss | Email) highlights some piece of historical arcana that may (or may not) be relevant to today’s college basketball landscape. This week: what could have been for the 1987-88 Temple Owls.

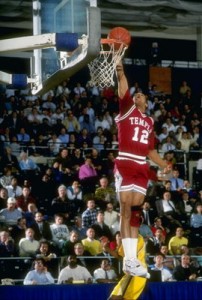

It wasn’t as if they needed that much help. After all, they’d won 32 games the previous season. The Temple Owls had three senior co-captains and a junior starter. And of course they still had Coach, whose no-nonsense basketball lessons made magic, even as they frustrated opponents and occasionally his own players alike. But when a player possessing such rare gifts as Mark Macon does comes along, you don’t say no, and you don’t toss him on the bench. Macon was a breakthrough recruit for John Chaney – the crusty, controlled Temple head coach – who knew by the time Macon showed up on campus what he had been sent, and he rightly treated the freshman accordingly.

“People ask why we allow Mark to do so much,” Chaney told Sports Illustrated in 1988. “No one asked why Kansas threw the ball to Wilt the minute he stepped off the plane. Mark’s our breakdown guy. He can beat you creating, with the dribble or the pass. He knows the game. He’s simply the best at his age I’ve ever seen.”

For a man whose idea of compliments means letting you only run gym stairs and not wind sprints, this was glowing praise indeed. But the kid deserved it. You’d never think a 32-win team would have a missing piece, but Macon was that piece. His scoring, his quickness, his levelheaded production, was what turned a good Temple Owls team into the best team in America for most of the 1987-88 season.

But he was also, when the end came, even as a freshman, the one on whose shoulders fell the blame, if not from his team and his coach, then from the assembled masses watching in the arena and at home on TV. Fair? No. But as Chaney, or Macon, will tell you, life isn’t about fair. It’s about work.

No one gave John Chaney much of anything; he took it or worked for it. Some of that was just his personality, but much of it was growing up at a time when young black men weren’t given anything but grief and a whole lot of ‘No.’ That’s what Chaney found out when his family moved to Philadelphia when he was just 14. Quiet and scared, embarrassed about his clothes and his Florida drawl, Chaney was just another poor black kid with no confidence and no future in a sea of such struggles, and with a home life that left him questioning everything. But Chaney was lucky in that he found something to believe in, and more importantly, to make him believe in himself. And it wasn’t a woman and it wasn’t a job and it wasn’t a favor. It was basketball.

Basketball made Chaney a man because Chaney made basketball a war: with himself and with whoever tried to take it from him. As many stories abound about Chaney’s temper and anger as do about his immense ability to play and coach the game. There’s the one about him literally tackling someone who beat him twice with the same move. There’s the one about him spinning a tray of glasses of water on one hand while dribbling with the other. The one about how he broke someone’s ankle who tried to swipe the ball from him. And the one where he threatened to kill an opposing coach. OK, the last one we all saw. But the others: Tall tales? Hard to say now, because there are nuggets of truth in them. Then, too, there are some facts: Philadelphia Public League MVP; 2,000-point collegiate scorer; NAIA All-American; Eastern Basketball Pro League MVP; Division II national championship-winning coach. And then these facts, too: no scholarship offers from the Big 5; No NBA interest after college; No Division I coaching jobs until 1982.

But Chaney never bowed, maybe because despite the hard luck, the bad politics, the injustice, how he took it was that nothing less than perfection would be acceptable, whatever the reason. He took all those hard lessons he learned and put them squarely in his heart. And now he would do the same for kids at Temple, for kids – often black, poor, fatherless, scared like he was once – who needed some lessons in what was going to be given and what was not.