Kellen Carpenter is an RTC contributor.

Last year, as you are probably aware, Duke won it all. They enter this season as the easy top pick in all the national polls and the consensus favorite to cut down the nets in the early spring of 2011. With Kyle Singler and Nolan Smith sticking around for one last hurrah, a sensational recruiting class starring the incredibly skilled Kyrie Irving, and Coach K masterminding things as usual, picking Duke as the best team in the country is pretty easy. Duke is going to be very, very good this year. Here’s the real question, though: Will this year’s incarnation of the Blue Devils be as good as last year’s? The consensus seems to be yes, but there is reason to lend an ear to dissenting voices crying out from the wilderness.

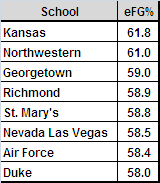

The reason has to do with offensive efficiency and may need a little explaining. Last year Duke was easily the most efficient team in the land on offense. They did this not by shooting the lights out (though they shot well), but by each player making sure they did other things to help their team on offense. Let me clarify: when I talk about “offensive efficiency,” I am talking very specifically about the Dean Oliver conception of it, which is a simple measure of how well a team scores per possession given a key Four Factors. The Factors are effective field goal percentage, turnovers per possession, offensive rebounding, and free throw rate. So while Duke was only moderately good at shooting the basketball last season (#92 in D-I), they made their opportunities count by rarely turning over the ball (#15 in D-I) and rebounding their misses at an astounding rate (40.3% of misses, good for #7 in D-I). The low turnovers and superb offensive rebounding are what made Duke’s offense so efficient and deadly, despite good-but-not-great shooting and a very average rate of getting to the free throw line (#158 in D-I for those who care).

Duke May Miss This Big Guy More Than Expected This Season

So, here is where we get to the trouble: Duke’s success at preventing turnovers and getting offensive rebounds, which strongly drove Duke’s overall success, depended largely on the efforts of two players. Those players, in case you can’t guess, are the departed Jon Scheyer and Brian Zoubek, to whom the Blue Devils are probably more indebted to than they realize.

Obviously, while Scheyer was the team’s leading scorer and his scoring contributions will be missed, his value to Duke went far beyond points. Scheyer was the team’s primary ball-handler and play-maker and did this ball-handling and play-making virtually mistake-free, which is astonishing. Despite having the most opportunities for a turnover, Scheyer coughed up the ball less than any other player on the team. Now while Nolan Smith and Kyle Singler should rightfully be credited for their skill at taking care of the ball, let’s be clear: Scheyer’s mistake-free play-making will be missed, and as good as Kyrie Irving is, it’s highly unlikely that a freshman point guard will be able to match Scheyer in this regard. It’s in fact very likely that the Blue Devils will turn the ball over a lot more than last season.

And if it’s very likely that turnovers will go up, it’s almost certain that offensive rebounds will go down. The incredible success of Duke at offensive rebounding is almost entirely owed to Zoubek, who not only led the ACC in having a name that sounds the most like a Pokemon but also was the best offensive rebounder in college basketball. By way of example: Duke had eleven offensive rebounds in the championship game against Butler, and Zoubek had six of those. This type of performance from the 7’1 big man was the norm. Now, Zoubek is gone, and his heirs in the frontcourt have yet to display anywhere near his level of skill at yanking down misses. While Zoubek grabbed 21.4% of the Blue Devils’ misses, the next best rebounder, Miles Plumlee, managed to grab only 11.1%. Mason Plumlee’s 9.1% and Ryan Kelly’s astonishingly poor 2.9% don’t offer much cause for hope either. These numbers considered, it seems very unlikely that Duke will be able to match last year’s incredible effort on the offensive boards.

Turnovers will probably increase and offensive rebounds will probably decrease, which means offensive efficiency is facing a drop, even if Duke somehow manages to keep up its world-class defense and replace all other lost offensive production. Now, am I saying Duke is going to be bad? No, I’m not. Duke will be very good, but unless a couple things happen, they won’t be in the same class as the national champion 2009-10 team. What we are probably looking at is something closer to the 2007-08, or 2008-09 vintage Duke, which is good for about the same regular season record but with a few more particularly surprising losses and a much shorter postseason. That said, here are some other things that could happen: Duke’s shooting this year could be so good that drops in offensive rebounding and a rise in turnovers could be totally offset. Kyrie Irving and the other rookies could be even better than John Wall and the Kentucky freshmen were last year, making everyone forget about Scheyer and Zoubek. Either of those things could happen. The conclusion is this, though — lots of things go right for Duke and I never count Coach K out, but the improbable is improbable, the unlikely remains unlikely, and “could” isn’t the same as “will.” That’s as true in Cameron Indoor as anywhere else in America, so let’s pack up our laurel wreaths and anointing oils until 2011.