Revisiting Mark Emmert’s Baseball Model Quote

Posted by rtmsf on August 23rd, 2010Last week we wrote a piece outlining the reasons behind our opinion that NCAA President-Elect Mark Emmert had made a mistake in publicly supporting the MLB model of amateur player draft eligibility. Emmert stated on a local radio show in Seattle that he believes that the NCAA should work with the NBA to enact a model mimicking baseball whereby high school players could choose to go pro immediately after their senior year, but those who went to college would have to remain there for three years. As we clearly stated at the time, all of this discussion from the perspective of the NCAA is merely for the sake of argument because the NBA is going to do what the NBA thinks is best for itself, and if that means requiring one, two or fifteen years of “experience” out of high school before player entry, so be it. The NCAA is virtually powerless in this regard.

Nevertheless, taking the position that it is the mandate and duty of the NCAA President to act in the best interests of his organization, we outlined a number of reasons why Emmert is mistaken with the baseball solution. Without delving into all of them again, the basic gist is that NCAA basketball needs marketable stars to support and enhance its product, recruiting will become even more difficult than it already is for coaches and schools, and players need the extra time to develop their games because so very few are actually ready to perform at a professional level immediately out of high school. Response to this piece has been mixed. Eamonn Brennan at ESPN.com seemed to understand the point we were making about Emmert and his role, but he expanded it to a more philosophical argument about whether forcing prospective NBAers into NCAA apprenticeships is “right.”

Rush The Court is right to say that’s not in the best interest of college basketball fans, or coaches, or universities, all of whom benefit from the compulsory one-year apprenticeship currently being served by even the game’s most League-worthy talent. It’d be much better if all players had to stay for three years; we’d get John Wall for two more years! Awesome! Where do I sign? But that’s wrong. John Wall should be free to pursue his NBA career. He should have been free before he ever stepped foot on Kentucky’s campus. College, as they say, isn’t for everybody. In proposing a baseball-esque system for college hoops, Dr. Emmert did two things, both of them inadvertent: He made an argument against the well-being of college basketball, and for the professional freedom of college basketball’s prospective athletes. What it comes down to is: Which is more important?

We’ll answer. From the perspective of Dr. Emmert as (soon-to-be) President of the NCAA and Supreme Chief Protector of the Game, the overall interests of the sport and its continued success trump the “right to work” component of a handful of high school basketball players each year. His new job is to advocate for the NCAA as an entity, carefully weighing options to ultimately move the enterprise forward. Since 96% of the NCAA’s operating budget comes from the NCAA Tournament (media rights + revenue), he needs to remember where his bread is buttered. If he pushes for a baseball model that ultimately makes college basketball less interesting to casual fans and, therefore, the media, he’s not successfully performing his job. This is a classic example of where academic arguments about what is right/wrong fail to properly mix with advocacy, and once again gives us pause about Emmert’s ivory tower worldview.

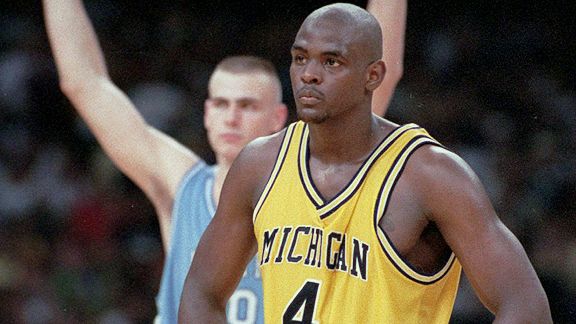

All that said, and as Kentucky blog A Sea of Blue expands upon, we certainly agree that the entire house of cards is exploitative from the player perspective. Mitch Albom’s book Fab Five (People You Meet in Heaven) recounts a much-repeated incident where Michigan star Chris Webber found himself without enough money at the mall one day to purchase food. As he walked by a sporting goods store and saw his own #4 UM jersey hanging in the window for sale, he became frustrated by the fact that seemingly everyone (Michigan, Steve Fisher, NCAA, Nike, etc.) other than himself was earning money as a result of his prodigious talents. This anecdote seems humorous now in light of later findings that Webber took hundreds of thousands of dollars from agent Ed Martin during those years, but the story illustrates how one-sided the system remains, even nearly twenty years later. Elite players are still generally no more than serfs for the one or two years they’re under the auspices of the NCAA (three years for football), contributing mightily to the billions of dollars of revenue they’re enabling while seeing very little in return. This is unlikely to change.

The larger point we’re trying to make here with respect to President-Elect Emmert is that it is not his job to suddenly make NCAA sports just, equitable and fair to the players whose talents are being exploited. He will not be called upon to advocate for the Chris Webbers of the world because the Chris Webbers of the world didn’t put him in that position — rather, the college presidents did. Therfore, his duty, much like the CEO of a major company, will be to protect the organization’s assets and push the enterprise forward so that in 2020, the NCAA can ask for two or three times as many billions of dollars in media licensing fees. We’ve explained to him how he should go about getting there (hint: making things more like college baseball isn’t the answer); it’s up to him to decide whether to listen.