Gladwell’s Theory on Full Court Pressure is the Only Outlier Here

Posted by nvr1983 on May 5th, 2009Everyone’s favorite contrarian and make-sense-of-the-world guru, Malcolm Gladwell, wrote a provocative piece in this week’s New Yorker that is making the rounds among the hoops blognoscenti today. Gladwell, the author of such fantastic thinking-man’s books such as The Tipping Point, Blink and Outliers, is one of our favorite writers, one of the few in the industry for whom we’ll actually make a specific trek to the book store and pay for a hardcover (!) edition shortly after his new material arrives. So when we say we’re a major fan of his writing, thinking and (ahem) moral clarity, we’re not joking. In RTC’s view of the world, Gladwell is Blake Griffin and the rest of us are merely the rim (or a hapless Michigan defender, take your pick).

Well, except for today.

Gladwell’s Argument

The article is long, but Gladwell’s thesis focuses on a story about a girls’ junior league basketball team located in Silicon Valley, filled with 12-yr olds who admittedly weren’t very good at the skillful parts of the game, but they could run and hustle and were able to win their local league and make the national tournament based upon their reliance and perfection of a strategy that any team can employ: the use of full-court pressure defense. In his argument, Gladwell successfully interweaves the biblical story of David vs. Goliath with quantitative analyses of historical military strategy and modern basketball, ultimately concluding that the Davids in every facet of competition have a much better chance of winning by simply changing up how the game is played.

Using his typical mixture of anecdotal and statistical evidence, Gladwell argues that for a David to have a chance at beating Goliath, he must do two things. The first thing – outwork Goliath – is a simple enough concept; but, more importantly, the second requirement is that David must also be willing to do something that is “socially horrifying” in order to change the conventions of the battle. For example, David knew he couldn’t defeat Goliath in a traditional swordfight; so he reconsidered his options and decided instead to pick up and throw the five stones by which his opponent fell. Gladwell likens this strategy to the one implemented by the girls’ team’s coach, Vivek Ranadive, an Indian-born immigrant who had never before played the game of basketball. Noting that his team wasn’t skilled enough to compete in the traditional half-court style of basketball played by most teams at that level, he instituted a full court pressure defense that truly confounded their opponents. Using Gladwell’s model, the press was a socially horrifying construct that allowed Ranadive’s team a chance to compete with their more pysically talented contemporaries. And compete they did, all the way to the national tournament.

Given the purported equalizing effect of the press, Gladwell asked why isn’t the use of full-court pressure defense more commonly used in organized basketball? He cites Rick Pitino as one of the most successful adopters of the strategy, particularly with his 80s Providence and 90s Kentucky teams, but other than a few coaches here and there over the years, in his estimation the strategy remains largely underutilized (Mizzou’s Mike Anderson and Oklahoma St.’s Travis Ford, a Pitino protege, say “hi”).

Why It’s Wrong

We’re somewhat concerned about a lightning bolt striking us when we say this, but Gladwell completely misses the mark on this one – the full court press as a strategy works great when you’re dealing with 12-yr old girls whose teams are generally all at roughly the same skill and confidence levels (i.e., not very good), but as you climb the ladder and start to see the filtration of elite talent develop in the high schools, it actually becomes a weapon that favors the really good teams, the Goliaths, more than that of the underdogs. The reason for this disparity is simple – successful pressure defense is a function of phenomenal athleticism (quickness, activity and agility) more than any other single factor, and the best teams tend to have the best athletes (not always, but often). That’s why the early 90s leviathans of UNLV, Arkansas and Kentucky were so unbelievably devastating – they each could send wave after wave of long, athletic players at their opponents, which were usually slower, less athletic and shallower teams.

Gladwell confirms this when he talks with Pitino at length about the 1996 Kentucky dismantling of LSU, when the Wildcats went into the locker room with an 86-42 lead as an example of the devastating consequences of a great full-court press. No argument there, but where it breaks down is when he fails to recognize that 1996 UK team was one of the best and deepest teams in the last quarter century of college basketball. Nine players saw time in the NBA from a team who steamrolled most everyone they came into contact with that season. The LSU first half was Exhibit A of the destruction, but they were far from the only one, and for Gladwell to use this example to somehow make a case for full-court pressure defense assisting the Davids pull off an upset is borderline absurd!

The other factor that Gladwell doesn’t discuss in his piece is that teams at the highest levels of basketball usually have guards who can beat pressure by themselves (not typically found at the 12-yr old level). There’s a very good reason that you almost never see a full-court press in the NBA, and it’s because point guards like Chris Paul and Rajon Rondo are nearly impossible to trap in the full-court. Every NBA team has at least one player who can easily negotiate any backcourt trap, which will lead to an automatic fast break advantage and two points at the other end – a coach of an underdog employing this strategy on a consistent basis will soon be in the unemployment line if he tries this too often. This is obviously less true at the collegiate level, but there are enough good guards at the top programs that similarly make full-court pressure a relatively futile effort. Are you seriously going to trap Ty Lawson or Sherron Collins for an entire game? Good luck with that strategy.

Conclusion

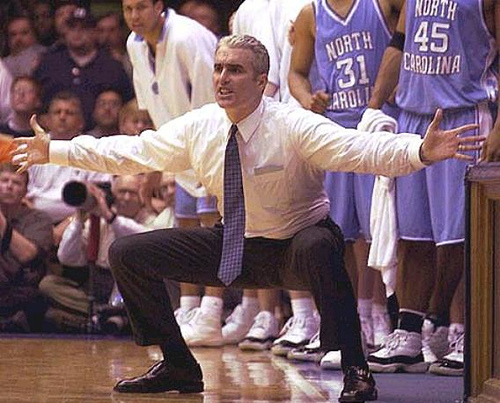

What’s particularly ironic about Gladwell’s conclusion that full-court pressure defense could act as the great equalizer in basketball is that a byproduct of this strategy is that it speeds up the game. Yet, the tried-and-true method for less talented teams to have a shot to beat their more talented counterparts is to slow the game down. Taking the air out of the ball became such a problem in the late 70s and early 80s that the NCAA instituted the shot clock to eliminate 24-11 abominations like this one. Even former UNC coach Matt Doherty employed a modern shot-clock version of the strategy in a 60-48 loss against #1 Duke in the 2002 ACC Tournament. We’d never say never about Doherty’s coaching acumen, but we would be seriously shocked if he had considered pressing Duke (and Jason Williams) as a viable strategy to pull off the major upset. It is Doherty, though, so you never know.

Gladwell, as always, wrote a thought-provoking article that told a fascinating story about Vivek Ranadive’s team of twelve-year old “blonde girls.” He failed, however, when he made a logical leap from youth league girls’ basketball to the elite levels on the assumption that such a strategy would work similarly for lesser talented teams. It’s a fair assumption that was likely made by someone not as familiar with the intricacies of high-level basketball, but our job here of course is to set the record straight. If we ever end up coaching youth league basketball, though, it’s now clear what our first practice will focus on.

Oh, damn you all to hell.

http://www.dearolduva.com/basketball/zigging-while-everyone-else-is-zagging/

While I agree with your conclusion that a pressing defense is less effective at higher levels of basketball and that it is not necessarily a sound strategy for the Davids of the basketball world, I think the key point that you mention is in this phrase: “12-yr olds who admittedly weren’t very good at the skillful parts of the game, but they could run and hustle”…

For a team that is not a particularly strong shooting team, or a team that doesn’t run sound precision offense, but has the advantage athletically, the press (or any up-tempo style) can take the advantage away from the more precise and skilled team and shift it to the team with the greater athleticism. And, frankly, I think that is a truism that holds from the lower levels of basketball right up to the NBA level.

Andrew, great point. When you run into situations where the “David” is actually the more athletic team, then a pressure defense is a good way to equalize things.

At the NBA level, that almost never happens because all the teams are super-athletic.

But at the college level, you’re right. I’m reminded of Mike Anderson’s UAB teams or Pitino’s early Providence and Kentucky teams, where they were able to pull substantial upsets employing that defense. Pitino’s seminal use of the three-pointer as a major offensive weapon was also an important element of that strategy.

This is a great response. Admittedly I’m a bigger college football fan than college basketball fan (except IU basketball that is!) but you hear this argument about the option in college football too. The reason you never see option football in the NFL is that every linebacker can run from sideline to sideline and safeties are so fast they get to the line too quick so the QB or RB end up getting hammered in the open field. In college football with an elite level team, the option works fantastic but when the athleticism is equaled out, it’s not such a great strategy. I guess if you are playing pee-wee football with the fastest guy in the league, you should be running option because he can get to the edge and turn the corner faster than anyone else.

It does happen from time to time in the NBA, although given the rules there (24 sec shotclock, 8sec timeline), it isn’t quite as apparent. A good example, although somewhat more subtle than what was discussed in this article, was the Lakers/Celtics finals last year. The Lakers (arguably) had the more “skilled” team (which is a completely subjective comment to make, considering that the Celtics had some seriously skilled players), but the difference in the series was the athleticism-edge that guys like Rondo, Perkins and Garnett (not to mention some of the bench players) had over guys like Fisher, Gasol and, say, Walton. It’s not like the Celts went press-heavy in the series, but they definitely applied more pressure and upped the tempo.

Of course, this gets into my whole pet-peeve where the NBA skews towards “athletes who play basketball” over “basketball players who are althetic”, but that is a topic for another day.

I’m gonna have to read this article.

I am reminded of the UNC-Loyola Marymount second round 1988 NCAA’s. Loyola did something like this, they just did it on the offensive end. They did not really concern themselves with defense nor did the shot clock come into play. They wanted to launch the first available “good” shot. Of course their definition of a “good” shot and the rest of the college world was two different things. This was an offense that was overwhelming teams, lesser teams. When they ran up against a team that had just as good athletes and that played more as a team, the outcome was not quite the same. Loyola may have taken a shot 5-8 seconds into the shot clock but UNC took one 8-10 seconds into it, with that one extra pass, the “team” won. I remember J.R. Reid standing along the foul line and shaking his head at the Loyola players and saying, “Not today fellows.”

10 HIGHEST SCORING NCAA TOURNEY GAMES

L-M OVER MICHIGAN 149-115, 1990

UNLV OVER L-M 131-101 1990

ST JOE’S OVER UTAH 127-120, 1961

OKLA OVER LOUS. TECH 124-81, 1989

UNC OVER L-M 123-97, 1988

IOWA OVER N-D 121-106, 1970

UNLV OVER SAN FRANCISCO 121-95, 1977

TENN-LONG BEACH ST 121-86, 2007

UTAH OVER ST JOE’S 120-127, 1961

ARKANSAS OVER L-M 120-101, 1989

I think the general point Gladwell is trying to make is that the press can be the great equalizer between basketball teams, which means his argument is inherently flawed. The difference between great and decent teams at the college level is usually athleticism. That’s why teams like UConn and Memphis always seem to be good – they get the most athletic guys, and mold them and their skill set to a certain system.

In that same note, athleticism is the key factor when it comes to running a successful press. Missouri is the perfect example this year. If they ran Georgetown’s offense, would they have been anywhere near as good?

Like anything in sports, a press will be successful on a case-by-case basis, and Gladwell doesn’t get that.