When to Fire Your Head Coach?

Posted by Andrew Murawa (@Amurawa) on March 15th, 2016Mixed in here with the end of the regular season and the start of the postseason is another far less festive time of the college basketball season: firing season. Johnny Dawkins, Joe Scott, Trent Johnson, Donnie Jones, Bruiser Flint, and Kerry Keating are among the names that have already received pink slips, while fans in various locales across the country are hoping against hope that their current coach joins such the list sooner than later. Sure, it’s a pretty macabre pastime to speculate on the status of a person’s livelihood and hope that he suffers a terrible indignity in a very public fashion. But somehow, such a thing has become a fundamental part of the sports landscape. As sports have increased in ubiquity and attention across the country, the level of patience granted to head coaches in all sports has drastically shrunk.

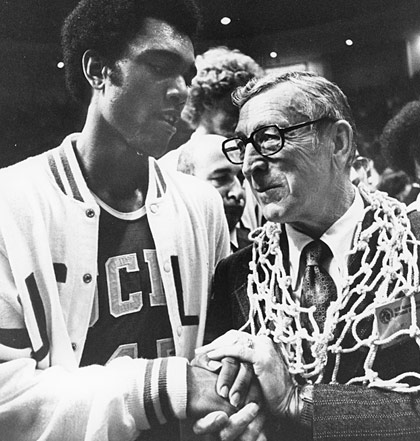

Given Today’s Standards, John Wooden May Have Been Fired A Full Decade Before His First National Title.

Need proof? Remember that John Wooden didn’t win his first NCAA title until his 16th season at UCLA and won just three conference titles in his first 13. Given today’s standards for coaches at the same institution, Wooden would have likely been fired in 1954 after a second straight year in which he didn’t even win the Pacific Coast Conference’s four-team southern division (the Bruins finished third of four teams in 1953 and second in 1954). Dean Smith? He didn’t win an ACC title until his sixth season at North Carolina and likely would have been fired in today’s environment after a 6-8 conference record in his third season. If he had somehow survived that, he certainly would have been crucified for making five Final Fours in the next 11 seasons but failing to win a single title; “can’t win the big one” would have been the lame complaint. Mike Krzyzewski? Duke’s head coach was very lucky to survive a bumpy start to his ACC career in which his second and third seasons resulted in combined records of 21-34 overall and 7-21 in conference play. He also came away empty in his first four Final Four appearances, and you probably know the rest.

Clearly the above examples show that it can pay to have a little patience. At the same time, you don’t want to hold on too terribly long when you know you’ve got the wrong coach. So let’s get to the question our title posed: When should a program fire its head coach? There’s no simple and easy metric, such as NCAA Tournaments and winning records and national titles, to determine this. What is a successful season at Washington State will get you burned in effigy at UCLA. And certainly the culture of a program, the graduation rates of students, the ability to schmooze and win over prominent boosters, the relationships with high school and AAU coaches – all of these factors are inputs into complicated equations that athletic directors across the country are paid salaries with many zeroes on the end to compute. To drastically simplify that equation, however, the answer is that it is time to part ways with a head coach when the momentum for a program has stalled out in obvious fashion and fresh blood is needed to initiate forward progress.

All of that was just a preamble to discussing the states of affairs at two Pac-12 basketball programs. We’ll first touch on Johnny Dawkins and Stanford as further preamble to discussing the fiasco at UCLA. On Monday, Dawkins was fired at Stanford after eight seasons that produced just one NCAA Tournament appearance (which miraculously turned into a Sweet Sixteen) and a pair of NIT Championships (note: an NIT Championship is not really a positive accomplishment in a power conference environment). Somewhat famously, Stanford athletic director Bernard Muir issued a silly ultimatum before Dawkins’ sixth season: NCAA Tournament bid or walking papers. Dawkins managed to sneak into the postseason that year (with a roster that should have been far more successful in the regular season), found a way to the Sweet Sixteen, and earned another season. In that next season, he took a similar team featuring multi-year seniors like Chasson Randle, Anthony Brown and Stefan Nastic and turned in a 9-9 Pac-12 season that put the Cardinal on the outside looking in. Following that performance, firing Dawkins would have been perfectly defensible.

Muir instead gave Dawkins another season — maybe because Dawkins is a stand-up guy who runs a clean program; maybe because he had a fresh start with a talented roster; maybe because of that run to the Sweet Sixteen. That additional season (2015-16) ended with his firing, but perhaps ironically, it may have represented Dawkins’ single best coaching job. Stanford lost starting point guard Robert Cartwright for the season to a broken arm just weeks before the season began. It then lost stud power forward Reid Travis to a stress fracture in his leg just nine games into the season. Dawkins transformed senior Christian Sanders into a passable point guard for most of the year (before having to suspend him), developed junior Rosco Allen into an all-conference type of player, and turned Michael Humphrey into one of the league’s best young big men. And somehow, with one of the thinnest and most mismatched rosters in the league, Stanford still won eight conference games.

Certainly momentum had stalled. Dawkins had done a good job on the recruiting trail, but it seemed as if he regularly failed to get the most out of those guys. Attendance at Maples Pavilion bottomed out. And following 13 NCAA Tournament appearances in the 14 years before he appeared on campus, his 1-of-8 batting average could no longer be ignored. Maybe Stanford could have given Dawkins one more crack at it while hoping for better luck on the injury front, but this spring seemed like the sweet spot where both Dawkins and Stanford needed a fresh start.

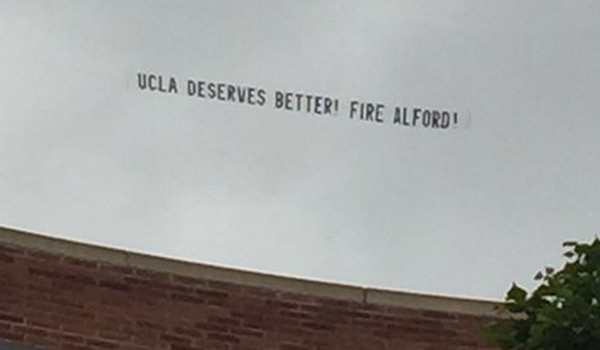

Let’s now turn to UCLA, where head coach Steve Alford just finished up his third season in Westwood in underwhelming fashion. His Bruins finished with a losing overall record for just the fourth time since Wooden retired in 1975, resulting in some fans petitioning athletic director Dan Guerrero to fire him, using a prop plane towing a banner in the skies around campus, reading “UCLA deserves better, fire Alford!” Let’s dig deeper. In Alford’s first season at the helm, he led the Bruins to a 28-9 record, second place in the Pac-12 regular season, a Pac-12 Tournament championship, a #4 seed in the NCAA Tournament and a trip to the Sweet Sixteen, where they lost to Final Four participant Florida. The following season, UCLA underwhelmed during the regular season, posting an 11-7 conference record and no notable non-conference victories, a resume that frankly should have been NIT-bound. But the NCAA Tournament Selection Committee threw UCLA a lifeline, which they ran with all the way to the Sweet Sixteen as a #11 seed. Then this year happened.

The fans now calling for Alford’s head were never enamored with the hire to begin with, claiming that a program like UCLA deserves a more high-profile coach. There was some controversy over how Alford had handled a sexual assault accusation when he was a head coach at Iowa in 2002. These fans will dismiss the first Sweet Sixteen as being won with previous head coach Ben Howland’s players (nevermind that Howland couldn’t take that group that far). Then they dismiss the second season by noting that the Bruins never should have been in the NCAA Tournament in the first place. They rightfully place blame at Alford’s feet for a season in which the team was inconsistent early, bad defensively throughout and uninspired at the end. With Alford clearly having lost at least a slice of the loudest part of the UCLA fan base, is it time for the institution to pull the cord and head in a new direction? Has momentum stopped? Of course not.

Sure, this season was bad and Alford correctly took the blame, saying he has to do a better job. But the needle for this program as a whole is still pointing up. Remember, one of the reasons UCLA ran Howland out of town (the same year he won the Pac-12 regular season title) was because of the dissolution of his relationship with southern California movers and shakers in the recruiting game. Alford needed to reestablish that connection, and boy, has he ever. Next year Alford will welcome in a recruiting class featuring four Southland recruits, highlighted by five-star players Lonzo Ball (rated as the best high school point guard in the nation) and T.J. Leaf (the #3 power forward in the senior class). He’s got commitments from additional local recruits in the 2017 class and has clearly reestablished those local ties. That success, in conjunction with those Sweet Sixteens, far outweighs (for now) the immediacy of the bad season the Bruins just turned in on the court.

Now, that doesn’t mean everything is all rosy in Westwood. Alford will have a load of pressure on him next season. That recruiting class plus a bunch of returnees means UCLA will be a trendy top 10 preseason pick next year. A Sweet Sixteen appearance alone may not be enough to cement Alford’s place in Westwood (just ask Steve Lavin), so he’d be wise to think about a Final Four. And it is clear that Alford cannot count on much fan support to aid his team on that quest. Pauley Pavilion is increasingly empty and quiet, and given the uproar at the end of this season (far louder than anything that’s happened in Pauley), next year will likely be worse. If the Bruins underachieve again, it’s possible that, depending on other factors, the right time to make a move would be one year from now. But for now, Alford will be back. And he deserves to be back.

Here’s the other thing, UCLA fans: Your expectations are entirely unrealistic. Yes, you’re one of the blue-bloods of the sport, but you’re one of the blue-bloods because of things that happened 40 or more years ago. Since Wooden retired 41 seasons ago, the program has added one banner. Those four losing seasons since Wooden left? All within the last 15 years. You’re no longer even the best program in your own conference. Remember how disappointed you were with the Alford hire? That happened because the position, with the insane expectations and nominal fan support, wasn’t attractive to guys like Brad Stevens, Shaka Smart, Billy Donovan. And with every stunt to express dissatisfaction with a guy who, in just three seasons (“rebuilding” your program from the horrors of Howland and his three straight Final Fours) has turned in a pair of Sweet Sixteens and some wildly successful recruiting classes, you’re making your job less attractive for the future. By all means,when Alford reaches the point where momentum has stalled and he’s outlasted his usefulness to your program, can him and move on. But at least pretend to be reasonable until that time comes.