Past Imperfect: The L Train Rolls On…

Posted by JWeill on November 23rd, 2011Past Imperfect is a series focusing on the history of the game. Every two weeks, RTC contributor Joshua Lars Weill (@AgonicaBoss|Email) highlights some piece of historical arcana that may (or may not) be relevant to today’s college basketball landscape. This week: the forgotten greatness of La Salle’s Lionel Simmons.

We all want to be remembered. We slog through our days hoping we can create something lasting, something that will point back to our time here and show we were worthy, that we made something of ourselves. Competitive athletes have even more impetus to do so, as it’s a big stitch in the very fabric of what they do. You win to be acknowledged. You win to gain affection. You win, quite honestly, to be remembered.

But what does it take to be remembered? It isn’t enough just to accomplish great things. It’s something more than that. Lots of players reach the pinnacle of the sport but remain afterthoughts once the bright lights are turned off. Too many times, players are remembered solely for the one big thing they did, right or wrong. Maybe it’s the game-winner at the buzzer, or the brain freeze that cost the team at the wrong time. Whole careers of effort are forgotten in lieu of the one big thing.

The 1989-90 NCAA basketball season was chock full of big things, stars and teams who made that season one that elicits a whoosh of nostalgia and basketball awe: powerful UNLV with Larry Johnson, Stacey Augmon and Tark “The Shark”; Georgia Tech’s “Lethal Weapon Three” of Kenny Anderson, Brian Oliver and Dennis Scott; Arkansas’ “40 Minutes of Hell” powered by Todd Day and Lee Mayberry; Duke’s choir boys Christian Laettner and Bobby Hurley and the boss choir boy himself, Coach K; LSU’s Chris Jackson and Shaq; and many more.

What most people recall about 1990 is the “Loyola Marymount” story. And indeed it was that season’s NCAA Tournament that immediately followed All-American Hank Gathers’ collapse and death, the event rendering Gathers’ All-American year almost a tragic footnote. Each spring you’ll see at least one clip of Gathers’ childhood friend from Philadelphia and college teammate Bo Kimble bravely playing on, shooting free throws left-handed to honor his fallen comrade.

We can remember all of this vividly, these names as familiar as many who’ve played in the 20 years since. But who remembers the other Philadelphia-bred superstar who finished his career that season? Ask fans to tell you who was named 1990’s Naismith, Wooden, Rupp, NABC, UPI and AP National Player of the Year and you’ll probably get a list of names like Larry Johnson, Gathers, Derrick Coleman or Jackson or any number of others. But it wasn’t any of those guys, whose household names we recall like distant cousins, the ones whose boyish faces we see in grainy analog footage each March.

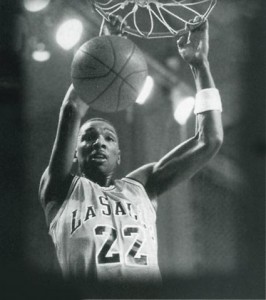

No, that player of the year was a lean and quiet local kid at La Salle University whose name was Lionel Simmons. Everyone just called him “The L Train.” You remember him, right? A touch over 6’6”, 210 pounds, underwhelming leaping ability and about as much pizazz as baked chicken? No, nothing? What about the guy who scored 3,217 career points in college, third most in NCAA history. No recollection, huh? Don’t be ashamed. You’re not alone.

Simmons was a kid from one of Philadelphia’s roughest areas, a kid from the projects. Like too many kids from neighborhoods across this country, it was nothing new to Simmons to see people around him engulfed by crime and drugs.

”There are drugs around and there’s violence, but to me it’s not a big thing because I’m used to seeing it and it doesn’t involve me. If you come from there, you accept it. And coming from that type of environment has made me hungry to want to get away from it,” Simmons told the New York Times.

Being the youngest of four, Simmons got used to taking a back seat, to watching and learning. Two of his older brothers served jail time. In the street games outside his home, he was often the last one picked, and he observed how the older, bigger kids played. By the time he was in high school at South Philadelphia High, Simmons had blossomed into a 6’5” slasher with great instincts. But even after helping his team to a city runner-up finish to Dobbins Tech as a junior, Simmons was only lightly recruited by the big schools. Instead, coaches flocked to Philly gyms to see another kid, Brian Shorter, a star at Simon Gratz High.

After Simmons averaged 32 points a game as a senior and tallied 21 points and 18 rebounds to lead South Philly to the Philadelphia Public League Boys Championship over University City in 1986, the college coaches still showed lukewarm interest, except for La Salle, with its Philly-bred former bar owner turned coach, Bill “Speedy” Morris. So that next fall, Simmons took his game from Broad Street and Snyder down to Broad Street and Olney.

Early on, it was clear that Simmons wasn’t just another overlooked but talented local kid. He was a star, albeit a thin one. Quietly efficient, never flashy, Simmons kept on pouring in points. Maybe it was that humble beginnings, or maybe it was being the son of a woman who worked extra jobs to help him reach his dreams. Whatever it was, Simmons was never cowed. The precocious kid hit a game-winner in an NIT win as a freshman, showing no hesitation. He scored 37 in the Dean Dome against North Carolina as a sophomore, the most ever by any opposing player.

Coach Morris surrounded his star with a bevy of local talent – Doug Overton, a Dobbins High School teammate of Gathers and Kimble, and Randy Woods from Ben Franklin High. La Salle may have been small time to some people, but they’d built a big time team from players right out of Philly. The L Train rolled on.

By the time he was in his third season at La Salle, Simmons was no longer under the radar. He poured in over 28 points a game that year, and following the season, NBA observers told Simmons he was a sure-fire lottery pick. But despite his moniker, the L Train wasn’t in a hurry to chug ahead. And more so, he wasn’t one to renege on a promise, especially the one he’d made to his mother to stay and finish his college degree. So Simmons took out an insurance policy and returned to La Salle for one more go around, a shot at NCAA tournament glory and to finish his degree in Criminal Justice.

The Explorers’ lopsided loss in the second round of the NCAAs the previous spring burned, but expectations for the next season were high for the Explorers, and especially for the returning Simmons. Things held to form early on, with La Salle winning each of its first eight games.

Then, on a chilly Saturday in January, the two hometown boys done good out West came back to Philadelphia to face La Salle and Simmons. Unlike Simmons, Hank Gathers and Bo Kimble had fled the rough streets they’d grown up on for the sun and relative peace of Southern California. Now, three years later, they were back, playing for a Loyola Marymount team that had become something of a phenomenon. LMU played a super-speed offense coached by Paul Westhead and averaged over 100 points a game. Gathers and Kimble were the team’s twin stars, posting video game numbers.

Simmons, whose high school had lost to Gathers’ and Kimble’s Dobbins Tech in the 1985 Public League championship, brought with him his own lofty scoring average and reputation, not to mention a team ranked 17th in the land and undefeated. For one night, the whole of college basketball had its eyes on the City of Brotherly Love, and they were not disappointed. Loyola won, 121-116. The two visiting Philly boys had 59 points and 22 rebounds combined. The L Train did his best to keep up, netting 34 and grabbing a whopping 19 rebounds, but it wasn’t enough. Still, on this night, old friends were not new enemies.

A few weeks later, on February 22, Simmons’ career total sat at 2,997 points heading into a conference game with Manhattan College. Following an early layup at the 5:30 mark, Simmons was fouled on a jump shot. Simmons, now a senior, raised on the gritty city streets, the kid who’d been at foul lines since he was a child, stepped up to shoot for point No. 3,000, his knees suddenly wobbling. Simmons sank the free throw and raised his arms to the sky. His teammates surrounded him and colorful paper fell from the rafters and erupted from the stands. The game was stopped for a massive celebration of Simmons becoming just the fifth player in NCAA history to accomplish the feat.

Even more remarkable? Not one time in amassing that stupendous sum of scoring did the L Train ever score 40 points in a game. Not once.

La Salle won that game, and every conference game it played that season, rolling to a one-loss regular season. Unlike the prior season, where La Salle had been a dangerous 13 seed in the NCAA tournament, a small school with big talent, this time no one would be overlooking the Explorers. They were expected to power through the Metro Atlantic Athletic Conference tournament and earn a top 5 seed in the Big Dance.

Things were going as expected when Simmons left the court of a MAAC tournament win over Siena, the game well in hand. As he was leaving, Simmons was told by La Salle teammate and childhood friend Bobby Johnson that their old friend and rival Gathers had died in a game a continent away. The nearly always stoic Simmons was overcome with grief, and left the floor to be with his mother, with whom he shed uncontrolled tears and wailed cries of “No, no no!”

Simmons had gotten to know Gathers well playing in Philly summer league games and had always maintained a gracious rivalry, whether facing each other in high school or on national television just weeks before. To the people of Philadelphia, Gathers was a symbol of pride, not to mention basketball stardom and hard work. That he was gone was unthinkable, especially to a friend and peer like Simmons.

After a team meeting, the La Salle players decided to continue on. To honor his fallen prep rival and friend, Simmons wrote Gathers’ name and number on his sneakers and wore a black armband as his team played for the MAAC conference championship and an automatic berth in the NCAA tournament. The L train’s teammates joined him in his quiet tribute. La Salle dispatched Fordham in the final and prepared for the NCAA tournament, where they’d earned a No. 4 seed.

La Salle dispatched SMU, coincidentally the same 13 seed the Explorers had been the season prior, before matching up with Clemson and its formidable interior duo of Dale Davis and Elden Campbell. Simmons played well, scoring 15 first-half points, and La Salle charged to as much as a 19-point lead in the second half. Trailing by 11 with just 12 minutes remaining, Clemson got hot, going on an 11-0 run to even the score at 55. Despite their Philly flavor, the Explorers couldn’t compete on the low block with Clemson’s frontcourt, especially Davis, who finished with 26 points and 17 rebounds. The Tigers took control for good with a late 15-3 run, and La Salle eventually fell, 79-75, ending a sterling 30-2 season, and the L Train’s career.

Simmons’ college adventure was over, but during the course of four years, the L Train had managed to break all kinds of records. He became the only player at the time ever to score 3,000-plus points and grab 1,100 rebounds in his career. The only one. He’d averaged 24.6 points a game for his career, and scored in double figures a stunning 115 straight games, still the NCAA record. Only five players have more rebounds than his 1,429 in modern NCAA history.

Maybe most importantly for a guy like Simmons, La Salle, the school he’s stayed home for, compiled a record of 100-31 in his four years and reached three straight NCAA tournaments, winning two games. He’d proved, always quietly and efficiently, that he belonged with the big boys, the older boys, the ones who would not pick him. He’d accomplished the goal he promised his mother, and graduated on time with his degree. Along the way, Simmons impressed everyone with his humility, grace and kindness.

Simmons was drafted by the Sacramento Kings 7th overall in the 1990 draft, a draft that featured a who’s who of basketball stars. He would get off to an All-Rookie start before injuries took their toll and cut his career short. His pro career would elicit more shaken heads than accolades, but that’s OK.

As it turns out, Simmons is remembered after all. He is remembered by the kids he spoke to at junior high schools around Philly and by the teachers who saw him work as hard at his studies as he did at his hoops. He is remembered by all those who saw his genuine emotional reaction to losing his friend Hank Gathers and by Philadelphia basketball fans, who later voted him the best Big Five player in history. Simmons is remembered because Simmons remembered where he’d come from, and where he wanted to go, and he didn’t veer from that path. He remembered there was more to living than just scoring and winning. There was more than being the L Train. There was being Lionel Simmons.

“That’s just Lionel,” his coach Speedy Morris said in January 1990. “I’ve got a stack of letters from principals of junior high schools thanking him for going there to speak. I didn’t even know he was going. He does it all on his own.”

His career-long teammate and friend Bobby Johnson put it this way:

”Me and Lionel have known each other since elementary school. He’s a caring guy, and he looks out for his friends. When somebody says Lionel Simmons, all you think about is good things.”

Sounds like someone worth remembering, doesn’t it?