Past Imperfect: Kicking in the Door

Posted by JWeill on February 17th, 2011Past Imperfect is a series focusing on the history of the game. Every Thursday, RTC contributor JL Weill (@AgonicaBoss | Email) highlights some piece of historical arcana that may (or may not) be relevant to today’s college basketball landscape. This week: the swift rise and fall of Cleveland State’s Kevin Mackey.

The question is deceptively simple: how much is too much too fast? For Kevin Mackey, the answers to these and other questions came too late – years and years too late – to save him, and his program, from himself. For the coach of the outlaws, the misfits, the ones no one wanted, the coach with all the answers to basketball questions, there were no answers to the questions about life, about how to handle it all after you’ve tasted the big time, after you’re somebody.

Indiana had no answers for Mackey and his boys that night, that’s for sure. But that was by design. Mackey knew from experience that no one who’s anyone answers the polite knock at the door. They either don’t hear you or act like they don’t. They’ll look out the window and see you standing there with your hair all wrong and your clothes all wrong and your everything all wrong, and they’ll just shut the shades and stay quiet. Don’t let him in. He’s trouble.

So that’s why you don’t knock politely on the door. You kick the door down and tell them, show them, that what matters isn’t your hair or your clothes or anything you can see but that you are capable of kicking the door down. That’s what they pay attention to.

Kevin Mackey had been kicking doors down for a long time before he got noticed. First as a high school coach back in Boston, where he kicked to the tune of three straight championship seasons at Don Bosco. Then, level mastered, he moved on to Boston College, where scouring the dark corners of the Northeast for hidden gems he helped Tom Davis and then Gary Williams rattle some folks, too. B.C. is where Mackey showed he could bring in the kids no one else could, the Michael Adamses and John Bagleys.

Boston College can be a tough place to get noticed. Despite being a cradle of future winning coaches, it was always a place you had to scrap and claw and kick to get noticed. That was just fine for a guy like Mackey. The harder, the better. And every year they took another step. Had to overcome Rick Kuhn and Henry Hill and all that point shaving business and just kept fighting for everything they got. And because they fought a lot, they got a lot. Like a Big East regular-season title in ’81. Like the NCAA Sweet 16 the same year. With Mackey still bringing in the tough kids, the kids with nothing to lose, and Dr. Tom still coaching them, the Chestnut Hill gang almost made it all the way to the Final Four in ‘82, shocking Depaul and Kansas State and nearly taking out Houston. Williams came in and, with Mackey, kept the whole thing going forward. B.C. finished first in the Big East again. Only a man as big as Ralph Sampson could end the run, which Virginia did in the second round of the ’83 NCAA tournament.

Having been passed over for the B.C. job, now it was time for Mackey to knock down his own doors. He knew what he wanted to do, now he just needed a where to do it. How about Cleveland? Another place you have to make a lot of noise to get noticed. When Mackey took over the Cleveland State basketball program, it had never before won 20 games in a season. Came close a few times, but this just wasn’t the place you go to win 20 games in a season. Mackey the coach knew this, but he also knew exactly what he wanted to do. He wanted to run, and trap, and kick those barriers to the big time down. And he knew how’d he’d get there – the same way he’d gotten this far: by getting the guys with nothing to lose, making them believe they could kick through a wall and then letting them loose on all the walls of the world. So that’s exactly what Mackey did. He brought in kids who had less than nothing to lose.

“I went after guys who had fallen through the cracks, who weren’t on the radar, wrong size for the position — hungry, aggressive kids with chips on their shoulders, something to prove,” Mackey said later in an interview.

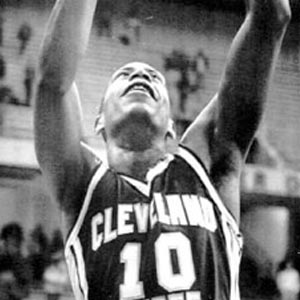

Most of these guys had never been given a chance to begin with and here was a coach who gave them one. You play hard for a man like that. Whether you’re a kid who worked as a house painter while getting his GED, a transfer from Ohio State or Alabama or some other place you weren’t wanted, or just a guy with a nickname like “Mouse,” “Fast Eddie,” “Identified Flying Object” or “Iceberg Slim,” you’re one of the guys Mackey chose to unleash on the world with a chip the size of Cleveland on their shoulders. You will play hard. Mackey barked at them with his Boston Irish accent, coached them up, wound them up into what he called the “Run ‘N Stun,” a 94-foot blitz attack of pressing defense and layups and dunks and rebounds and steals, and then loosed them on an unsuspecting basketball universe. Because, really, why just knock the door down when you can blow it off its hinges?

In Year 2, Mackey brought Cleveland State 21 wins: a first. But it wasn’t enough. Not even to even get an NIT bid. At a place like Cleveland State you had to be louder than that to get noticed. So Mackey put in place a team that would get noticed, all right. How’s 13-1 in the conference sound? What about 27-3 on the season? How’s a 15-point pummeling of DePaul in Chicago? That loud enough for you? This time around, it was. On Selection Sunday, the players and coaches knew once their name was called that their foe in Round 1, Indiana, had no shot.

“Indiana just lost. Little do they know,” was how Mouse McFadden put it later.

Mackey had turned his little corner of nowhere into something, just like he knew he would. And his batch of basketball vagabonds and throwaways? They weren’t content with just making the tournament. Mackey wouldn’t begin to let that be enough. They were in the tournament to win it. After those 27 wins and a 14-game winning streak heading into the postseason, who was going to tell them differently? They knew what no one else knew: that without time to prepare for their Run N’ Stun, they had the advantage over whomever they played.

Bob Knight knew that, too. That’s why he spent all week after the brackets were announced telling his team not to take Cleveland State lightly, that if they did, they’d be back in Bloomington before they knew what hit them. But the Hoosier players didn’t listen or it didn’t matter. The first few Indiana possessions ended in steals. Meanwhile, Clinton Ransey was on fire. This less talented than usual Indiana squad had overachieved all season and had been matched up against the worst possible opponent for them: one with endless energy and bodies to throw at them, not to mention a giant chip on their shoulders. The pressure Mackey knew could rattle anyone was rattling the Hoosiers all game long. And Ransey just kept hitting. Behind All-American Steve Alford and Knight’s threats, Indiana put up a fight, but it wasn’t enough.

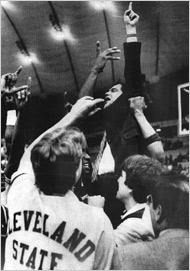

Game over. Mighty mouse Cleveland State 83, mighty Indiana 79.

In the second round, Mouse McFadden led the way as Cleveland State became the first 14 seed to reach the Round of 16 by beating St. Joseph’s. Mackey’s boys were cocky, riding high and didn’t see any reason they wouldn’t be playing in the Final Four in two weeks. Unfortunately, they missed the reason – all 7-foot-1 of him – standing right in front of them. David Robinson and Navy ended the Vikings’ magical season on a last-second tip-in in the Sweet 16.

Still, the Vikings were the new “it,” and their coach was riding the wave with them. Back in Cleveland, he was being called the King, and he was acting like it.

“I’d go to the best places, I’d go to the middle places and then I’d go to the worst places. And in the worst places, sometimes I’d feel like I was treated the best. I’d be in places at 3 or 4 in the morning, my big car out front, with all the bad guys,” Mackey told USA Today in 2004. But for the time being no one seemed to care.

* * *

Sophomore forward Paul Stewart was dead. Just two months ago, the Vikings had been the toast of the basketball world, Sweet 16ers, and now? An ambulance parked in front of the gym took a young man’s body away. Gone from a heart attack. And with him, some of that sweetness that had made Cleveland State a darling. Now it was a dark cloud that lingered over the team. Despite a preseason AP ranking and another 25 wins, Cleveland State wasn’t anyone’s darling anymore. They were just a team that didn’t have the same juice the second time around. A year removed from the spotlight, an NIT second-round loss surprised no one outside Cleveland. Meanwhile, everyone else had moved on. Indiana certainly moved on, adding a flashy JUCO named Keith Smart in the offseason and rolling all the way to the national title. Kevin Mackey and the Stun ‘N Gun were nowhere in Knight and his players’ minds the night Smart’s jump shot gave Indiana the 1987 NCAA championship.

Then, that fall, the NCAA came snooping. The powers that be eventually smacked the program with three years’ probation and a two-year postseason ban, sanctions relating to recruiting foreign players a few years before. That meant the 1987-88 season would be the last opportunity for two years at least to show the world what Cleveland State had to offer. No one knew at the time it would be the last time anyone saw Cleveland State in the postseason for 20 years.

* * *

There was no champagne toast around this table. No one here at the station was giving it up for the man who brought basketball glory to Cleveland. This table was all frowns, serious talk and serious looks. Hours earlier, a woozy, boozy, Kevin Mackey had been arrested for driving under the influence after he crossed over the center stripe moments after leaving a known crack house with his mistress. But Kevin Mackey didn’t get arrested that night. Cleveland State head men’s basketball coach Kevin Mackey got arrested, and, thanks to a tip-off, the local news media was there to film the whole thing. Never mind now that Mackey had just inked a brand new contract with the university that was to pay him over $300,000. July 13, 1990, changed everything.

The police eventually found traces of cocaine in Mackey’s system. The thing Mackey had been avoiding for so long, the thing he could not control, had caught up to him. He was a user. Cleveland State University fired him just six days later, telling the world that his actions “made a mockery” of the school’s moral standards. And just like that, it was over. Mackey was done. And with him went the Cleveland State basketball machine, the Run ‘N Stun, all of it.

Mackey went to rehab. Like it has been for so many others, John Lucas’ version of rehab meant more than just clean living. It meant starting over. Gone were the job offers and the money and the fame and the blur. In its place, a life to live, basketball or no basketball. Mackey found ways to stay in the game, at its lowest levels. USBL, Argentina, Korea. Wherever. Mackey had never done things the easy way, and he had no choice now. So he kept plugging away, coaching kids far from the NBA. He still taught them lessons about what it meant to be given up on, to be too small, too fat, too slow, too whatever. But gone was the fire that had once been all consuming. His days of busting down doors were over. Kevin Mackey was all kicked out.

* * *

Larry Bird doesn’t call that many people. He definitely doesn’t call people like Kevin Mackey very often. So when he called, Mackey listened. Bird had a proposition for this man he’d never met, this basketball pariah. Come work for me. Be a scout for the Pacers. Mackey knew it was a way back into the big time, even if it was a small scale. Besides, watching players and finding players was what he’d always done best. So Mackey took the job and began logging the miles he was already used to logging on basketball’s back roads. His head down, Mackey was now just another scout looking for hidden gems. Just like old times.

Meanwhile, back in Cleveland, something was happening. Former Rutgers coach Gary Waters had taken over the moribund Cleveland State program. Waters had been a big deal mid-major coach before, when he built Kent State into a MAC power. But the Big East had chewed Waters up and spit him out. Humbled and hungry, Waters built the Cleveland State program back up, brick by brick, using players who were too small, too slow, too something for the big boys.

And when Waters and his Vikings marched past Butler, beat them in the ’09 conference tournament title game to head back to the NCAA Tournament for the first time since the Mackey Miracle, it was all of them – Mackey, Mouse, Iceberg Slim, Vinnie Vandalism, all of them – that were headed back to the tournament, back to where they rightfully belonged. Now, two years later, Waters again has the Vikings looking primed for another dangerous tournament run.

Mackey will be watching. It’s his job to watch, especially since this Cleveland State team features an NBA prospect named Norris Cole, a hard-nosed guard from Dayton who plays like he has something to prove. Sounds like just the kind of player Mackey has always liked.