Behind the Numbers: Do Blowouts Predict Champions?

Posted by KCarpenter on November 24th, 2010Kellen Carpenter is an RTC contributor.

It’s been a hard-fought game. Every shot contested, players from both teams diving all over the court for loose balls, the crowd whipped into a frenzy. Bitter rivals, ranked teams, and it all comes down to one buzzer-beating shot. This is a good game. This is why we watch college basketball. Who wins? Who cares? Rhetorical questions can cut two ways, and this one is particularly vicious in matching it’s semantic zig with meaningless zag. On one hand, we gladly affirm the joy-of-the-game sentiment: Close games are their own reward, and if both teams played hard, we can walk away with a zen-like comfort at having seen a beautiful competitive spectacle. That said, there is a colder reading, one that isn’t as much fun, but may be just as important: Close games between evenly-matched teams don’t mean much of anything, it doesn’t tell us anything about how good either team is. No matter what is marked down under the team records, win or lose, the game is basically a tie.

Maybe you are preparing a protest: pulling out a tough win shows force of will, late-game execution, grit and guts. These are the best wins, you argue, because it shows you that the team knows how to win when it really matters. A team that can win when the going gets tough can win no matter the situation. Well, okay, hypothetical protester, time to drop the biggest open secret that everyone not on television knows: margin matters and, in terms of predicting future success, a win by one means about the same as a loss by one.

This makes sense with a little bit of thought. Basketball games are a long series of events each contingent on probability, and probability is a fickle mistress. Consider our hypothetical one-point game: In the second quarter, the power forward for one of the teams manages to take a barely-contested ten foot jumper and he has a 50% chance of making the shot. Half the time it goes in and half the time it doesn’t, the rest of the game unfolds in the same way and because of that one event, the team either loses or wins. In every other way, the team is just as good or just as bad as we always knew it was. One shot doesn’t actually change that. Did Butler lose the National Championship because they missed the final shot? Maybe, but they also missed eleven other three-pointers over the course of the game. Hitting any one of those would have won the game.

Is this an oversimplification? Yes, but it all speaks to a simple idea: That the difference between a one point win and a one point loss is really almost white noise. The idea isn’t just a philosophical buzz-kill, but rather a philosophical buzz-kill with implications: Winning by a little doesn’t mean much, but totally dismantling an opponent means a lot. If a team wins by twenty points, it means that they are very likely better than that opponent. Instead of just one lucky shot, they had ten lucky shots, and if you have that many lucky shots, then chances you aren’t so much lucky as good. There is meaning in blowouts. This is why just about every serious advanced-statistical ranking system takes into account margin of victory. That said, we don’t need to tear wide open Ken Pomeroy’s magical tempo-free machine to fully understand this principle, and instead, for an illustration we can turn to a different sort of numbers game.

In 2005, Aaron Schatz at Football Outsiders published a look at recent Super Bowl teams with each team’s success broken down into a few separate categories. He counted the times a team destroyed a terrible team (a “stomp”) and the times they won a close game against good opposition (a “gut”). In the ten years he surveyed, only once did a team have more guts than stomps. For good measure, he also counted up the times a team totally destroyed a good team (a “domination”) and the times a team barely beat a bad team (a “skate”). Unsurprisingly, a team that barely beats bad opponents doesn’t tend to have much success in the Super Bowl. What was more interesting was the fact that teams that won more blowouts (either stomps or dominations, although interestingly, stomps were more predictive than dominations) were far more successful than those with the most guts and skates. Recently, the very smart Neil Paine at Basketball Reference conducted a similar study using NBA teams and, lo and behold, the results came out pretty much the same: NBA teams that blow out bad teams (and good teams) win the championship more than teams that get those emotionally appealing gritty wins. Of course, here we are in the business of talking college basketball and not the NFL or the NBA, so the question remains open: What does a stomp mean in college basketball?

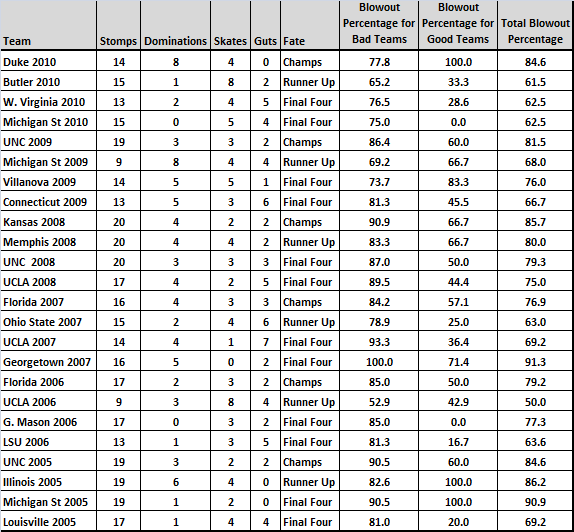

I am pleased to tell you that a very-preliminary, toe-in-the-data-pool, I-would-never-claim-this-is-scientific analysis points to the idea that Aaron Schatz’s point holds up even in college basketball (fully sortable data here). I looked at the regular season records of the Final Four teams from 2005-10, defining a “good” opponent as any team in the top 50 RPI (basically any at-large caliber team) and a blow-out as a win of ten points or more. I considered a win of nine points or less close and any opponent outside of the top 50 RPI, “bad.” Unsurprisingly, every one of the 24 teams examine had more stomps than any other kind of win. Also unsurprising if you buy the theory I’ve been explaining, every National Champion had the more or equal stomps than every other team in their Final Four, with the exception of 2010 Duke, which had one less stomp than Butler and Michigan State. If we were to switch from counting raw stomps to looking at the percentage of time each team blew out “bad” teams in their wins, we’d see that the National Champion has the highest (or tied for highest) stomp rate in five out of the six years examined (The exception in this category belongs to 2007 Georgetown, who stomped sixteen teams without a single skate).

Curiously, the data that I looked at follows the same general pattern as the NFL data in the sense that adding the domination data actually weakens the trend: the National Champion had the highest blow-out percentage against good teams in only three out of the six Final Fours. Which suggests, in a rather silly way, beating the living hell out of bad teams is potentially a better indicator of future success than winning against other good teams! Again this is a very preliminary and shallow look at the data filled with fairly arbitrary assumptions, but it’s a start. The world would gladly and eagerly receive a more expansive and magisterial survey of the correlations between these categories and future success. Until then, take these findings with a grain of salt, and try to find an extra degree of pleasure in the long train of inevitable non-conference November and December beat-downs. Compared to February buzzer-beaters and hard-fought conference struggles, these victories seem tedious, joy-less, and often-times boring. The narrow win over the skilled rival is just the best feeling, the narrow loss, the worst. Try to remember then, that these late-winter, closely-contested struggles are often simple luck. But those non-conference blow-outs? Well, those are the mark of a champion.

The bigger question is the predictive factor for teams as a whole: Can we make reasonable predictions that a team is a Final Four or Championship caliber team based on their percentage of blowouts? Are there teams not listed that had lots of blow outs bit DIDN’T make the Final 4?

The NBA works better because of similar schedules, where the NCAA allows team to schedule themselves… so more ‘blowouts’ might in fact be schedule related.

Hey Keith,

You are right on the money and there is a lot of work to be done to get some real answers. The use of percentages is meant to work around some of the scheduling problems inequities but even that isn’t totally satisfying.