Alpha Dogs, Traffic Jams, and Derrick Williams

Posted by KCarpenter on February 10th, 2011While we love to celebrate teamwork in college basketball, the truth is that the individual is much more fun. Balanced scoring is fine and tactically sound, but what we really love in college basketball is the virtuoso offensive performance, or as it is called in 2011, the Jimmer. And while the three-headed Devil from Durham may have won last season, perhaps this season, the one man show is back in style. It’s Michael Jordan’s fault, really. His competitive nature and unbelievable personal narcissism motivated him to incredible heights and made him largely unbearable to most of his contemporaries. His success provided a model for greatness that was easy to recognize and hard to argue with. There are lots of different names for the Jordan model, but Bill Simmons’ version is probably the best known: The Alpha Dog.

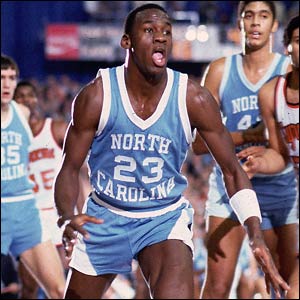

Simmons didn’t invent the concept or the term: lots of analysts, sportswriters, announcers and coaches have described the alpha dog model in one way or another over the years. The gist of it is this: A team needs an undisputed leader. The alpha dog is the go-to-guy on offense and is the guy who takes the game-winning shots. To win championships, you need an alpha dog. Jordan was an alpha dog (at least for the Bulls if not for North Carolina), and he is the primary reason his team won championships. Despite being a team game, you need an alpha dog to win, to demand the right to take the last shot. Guys who pass up the last shot aren’t alpha dogs: they are losers. At least, that’s the catechism. However, in the grand world of Simmon-isms, there may be another theory at play.

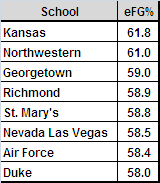

Specifically, I’m talking about the Ewing Theory, which in short, postulates that sometimes a team will play better without its star player, that the team will transcend the individual. Does this contradict the Alpha Dog theory? Well then it contradicts the Alpha Dog theory. Simmons, like Walt Whitman, contains multitudes. In any case, the Sports Guy has lots of examples, and anecdotally, lots of folks have seen this with their own eyes and believe it. It’s not too hard to imagine a scenario where this makes sense. The star is a volume scorer and fairly inefficient, and when the star is out of the game, the other players get more shots and more efficient shots. This is fairly intuitive and you can see the principle in action every Kentucky game. Terrence Jones is a sensational basketball player and undoubtedly incredibly skilled. That said, he is the fifth most efficient scorer on the team, but takes 30.5% of the shots. If he took fewer shots and his teammates took more, the team’s offensive efficiency would go up.

At Ohio State, Jared Sullinger uses, by far, the most possessions in each game, and for the most part, that’s fine. Sullinger is an incredibly efficient scorer with an offensive rating of 123.6 (points per hundred possessions). That said, Sullinger’s teammate Jon Diebler has an insane offensive rating of 139.1 and yet uses only 12.5% of Ohio State’s possessions. If I were to pretend you were naive here, you would then ask why Ohio State isn’t constantly feeding Jon Diebler. Fortunately, you aren’t naive and you understand that efficency is fleeting. Or if not exactly fleeting, curved.