Behind the Numbers: Considering Point Guard “Purity”

Posted by KCarpenter on November 10th, 2011Kellen Carpenter is an ACC microsite staffer and an RTC columnist. Each week, BTN will take an in-depth look at some interesting aspect of college basketball’s statistical arcana.

The phrase “pure point guard” is loaded. It implies that there is a Platonic notion of point guard which all mortal players can only aspire to. We are just fools in a cave looking at a shadow on the wall, but that is all we have when the purest conception of the point guard is beyond our field of vision. I can only assume that this unknowable figure looks something like Bob Cousy. It also implies that outside of “pure point” play, there exists a realm of impure play where the division of basketball labor isn’t as orthodox as it is inside Plato’s basketball cave.

In a point guard, “purity” is code for being a pass-first lead guard. To the traditional school of thought, the roles on a basketball team are strictly regimented: The point guard passes, the shooting guard shoots, but not as much as either forward. The center, near-immobile but Mikan-like in his hunger for loose balls has a single task: rebound the basketball and get it to the point guard. Of course, this idea of the traditional division of labor in basketball hasn’t really held since the days of Mikan himself. Modern basketball, by which I mean basketball since the mid-sixties, has embraced the hybridization of positions. Basketball has for years acknowledged the idea that team roles are mutable and that positions are flexible. While few have embraced the full-on positional revolution explicated by Bethlehem Shoals and the NBA-heads of the dearly-departed Free Darko, most of us have made peace with the idea that it’s okay for point guards to score occasionally. Kemba Walker and Jimmer Fredette were the break-out stars of the past college basketball season and both undoubtedly play point guard in a thoroughly impure way. If those guys aren’t pure then shouldn’t we all hope to be dirty?

In all seriousness, the concept of the purity of the lead guard is a silly concept to dwell on. Still, like all sports cliches, the idea persists because it’s a convenient way to sum up the play of pass-first point guards, who somehow pay homage to a golden era of basketball which is more than ancient history. Still the idea of the pass-first point guard is an intriguing one in this era of high-scoring combo guards. Like the crocodile, the pass-first guard is a relic of a by-gone epoch, a living fossil and a reminder of the dinosaurs who ruled the earth during that time. Is the crocodile a better predator than the tiger? This isn’t a debate that I’m interested in. The pass-first point guard, by mere value of their odd, antiquarian style is a unique species worth studying.

This is a long way to go to say that Kendall Marshall‘s game is old school, but that’s the point that I’m getting at. Luke Winn, in his first installment of the deservedly celebrated power rankings, put up an interesting chart that broke down the pass-versus-shoot tendencies of the point guards of the sixteen ranked teams. Winn notes that Marshall is the only player in the group that averaged more assists than field goal attempts over the course of the season. Looking at the top 100 APG players in the country last year using the versatile College Basketball Reference Player Season Finder, I calculated a quick and dirty metric of their pass-first tendencies by simply dividing the number of assists per game by the number of field goal attempts per game. While Marshall rates near the top of the hundred, he’s hardly the only pass-first guard in the country.

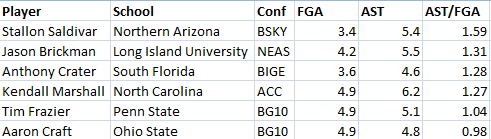

The Most Pass-First Of The Top 100 Assist Men of Last Season

Stallon Saldivar has the distinct honor of being the passingest guard in America last season. Of the one hundred players examined, only five managed to meet the criterion of getting at least one assist for every shot they took. Outside of Marshall and Aaron Craft of Ohio State who just barely missed the cutoff, however, the tournament relevance of these players and teams seems fairly questionable. If Saldivar distributes the ball in the desert in March, it’s unlikely that anyone will see it. Contrast this group with the players at the bottom of the list; the players with the lowest assists to field goals attempted ratio.

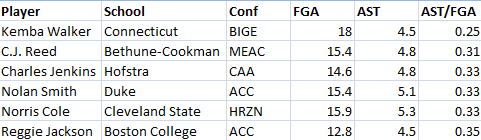

The List Of Shoot First Point Guards Includes Some Familiar Names

With the exception of C. J. Reed of Bethune-Cookman, this is a list of some of the biggest talents in college basketball last season. It’s no surprise that Walker, a veritable scoring machine, shot more than he passed. What is exceptional, however, is how thoroughly this group out-classes the first group. While none of these players quite match the raw assists per game of Marshall, as a whole, the number of assists per game is very similar on both lists. The shoot-first point guards are doing just as much assisting per game, they just happen to be scoring a lot as well. Not to compare crocodiles to tigers here, but wouldn’t you prefer a randomly selected player from the shoot-first list on your team than a randomly selected player from the pass-first team?

Regardless of the talent of the shoot-first guard squad, our focus remains on the very curious list of names that makes up the top of the pass-first list. Why do these players play with this odd style? The first thought that comes to mind might be personal limitation: Maybe these players don’t shoot because they are bad at scoring. Of course, that can’t be the whole story. Of the six players under examination, only Anthony Crater qualifies as truly-offensively challenged. What is it then? What is it about these players that has caused them to adopt such an idiosyncratic style of play?

The answer, of course, has only a little to do with the players, and a lot to do with the teams they play on. While most of the pass-first players are fine on offense, they by and large play on a team with one or more scoring savants. Saldivar spends most of his time passing the ball to Northern Arizona teammate Cameron Jones, who, outside of a certain player whose first name is Jimmer, took a greater percentage of his teams shots than anyone else in college basketball. Tim Frazier‘s backcourt partner at Penn State was none other than Talor Battle, a man who played the second most minutes for his team in the country and felt obliged to take a corresponding number of shots. While Anthony Crater may have passed the ball because of his own offensive shortcomings, he at least regularly got the ball to the slightly more efficient, yet significantly shot hungrier South Florida teammates Augustus Gilchrist and Jawanza Poland. In a similar vein, who can blame Marshall for passing the ball when it’s most likely going to Harrison Barnes or Tyler Zeller? Who would blame Craft for passing to William Buford and Jared Sullinger? Pass-first is less a personal playing style, but a pragmatic response to the personnel of the team. If a point guard is able to capably pass the ball to a teammate who is more likely to score, they should obviously do it. Are pass-first point guards the cause of successful offenses or are pass-first point guards merely a symptom of successful offenses? Should your team’s point guard pass more or shoot more?

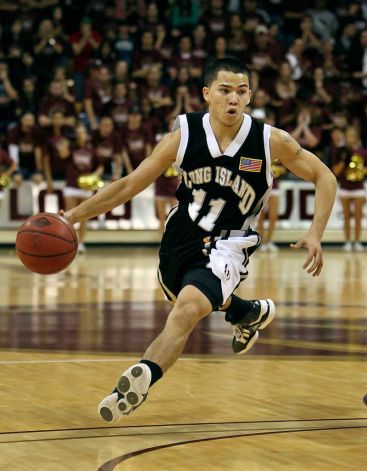

The pass-first mentality isn’t a sign of a particular breed of basketball sophistication. This style of play is a rational response to playing with teammates who can score the ball more effectively. With talented teammates in scoring position, the smart point guard passes more. If that same player had terrible teammates, his pass-first style wouldn’t benefit his team, but rather hurt it. This brings us to Jason Brickman and Long Island University.

A combination of excellent three point shooting and a keen ability to draw fouls made Brickman the most offensively efficient player on a fairly high-powered Long Island team. Yet, despite his team-best efficiency, he took a lower percentage of shots than any other meaningful contributor to the team. While the high offensive efficiency of a number of the freshman guard’s teammates is no doubt partially due to the keen-passing and deference of Brickman, two of the top three players in terms of usage rank eighth and ninth in terms of their offensive efficiency on the team. Now, while I can’t be certain that Brickman passed the ball more to these players than he should have, if we are going to credit the pass-first point guard when he allocates possessions appropriately, we must blame a point guard when the possessions are allocated unwisely. For Long Island, Brickman’s keen ability to share the wealth is one that is misused. The clever point guard distributes with a purpose in mind: effectively scoring the basketball. Distribution for the sake of distribution may win you the title of “pure point guard,” but it might also be hurting your team.

Sacrifice your purity, Jason. Embrace your inner ball hog. It’s for the sake of the team.

Watch for Brandyn Curry of Harvard to emerge from”under the radar”and prove himself to be among the elite pure point guards in the country.