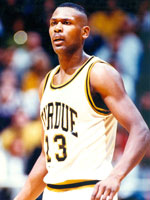

Past Imperfect: Big Dog Robinson’s Beastly Growl

Posted by JWeill on January 11th, 2012Past Imperfect is a series focusing on the history of the game. Every two weeks, RTC contributor Joshua Lars Weill (@AgonicaBoss|Email) highlights some piece of historical arcana that may (or may not) be relevant to today’s college basketball landscape. This week: the marvelous dominance of Glenn Robinson.

The Big Dog was shy. You wouldn’t believe someone with a nickname like that would be quiet, reserved and sensitive. But then again you wouldn’t believe a lot of things about Glenn Robinson, Jr.

To believe just how dominant — how beautiful to watch — the man known as Big Dog was in his two seasons in West Lafayette, Indiana, you first have to understand it takes more than talent to make a great basketball player. Every year, millions of kids start high school hoops with dreams of being the next big thing. Many have more innate talent than all but a small fraction of their peers. But whether it’s lack of focus or work ethic, lousy coaching or just lacking the will, the vast majority of those talented kids will never be better than average at basketball.

But those select few whose ability to do whatever they want on a basketball court – the capability to dominate every game — these are your superstars. And to be one of those, a player has to possess more than just athleticism, talent and more than just focus. These players must have something deep in their psyche that compels them, that propels them, beyond the abilities of normal athletes. And this brings us back to the Big Dog.

In the early 1990s, college basketball was changing. Gone were the behemoths that had dominated the college ranks for a decade. With the exodus to the NBA of Shaquille O’Neal and Alonzo Mourning in 1992, and the new prevalence of coaches running full-court, trapping defenses, a new need for versatility and ball-handling skills at nearly all five positions emerged. Suddenly, the demand for plodding centers was replaced by a demand for frontcourt players with backcourt skills.

This new breed of inside-outside forwards was led by a cadre of beefy but agile college big men, guys like Kentucky’s Jamal Mashburn, Wake Forest’s Rodney Rogers and Vin Baker of Hartford. Each of these players was an All-American, a top draft pick and an electrifying blend of power and finesse. But the best of that era’s “swing-bigs” was without question Purdue’s Glenn Robinson.

But what made Robinson so good was actually not even basketball-related. Raised on the rough streets of Gary, Indiana, the reserved Robinson was instilled early with an inner and outer toughness that took his already otherworldly hoops talents to a different level. Combining his immense physical gifts with a hunger for success and perseverance that can be borne only of struggle, Robinson reached that rare transcendence in sports that cannot be created solely by training and talent alone. Isiah Thomas had it. So did Larry Bird. And Glenn Robinson certainly did. His came from a natural place – his mother.

Robinson’s father was in and out of jail throughout his life. The elder Robinson left Christine Bridgeman when both were teenagers, and like too many inner city girls in similar situations, Bridgeman was left to fend for herself with a newborn. But Robinson Jr.’s mother had that steely resolve – the same resolve that would later show up so many nights in her son on the court – that wouldn’t allow failure. Like the time Glenn was struggling with his high school grades, and Christine marched into the coach’s office with her boy and informed the coach his star wouldn’t be on the team unless his grades improved. And guess what? They did.

As a star high school senior at Gary’s Roosevelt High, Robinson averaged 25.6 points, 14.6 rebounds and 3.8 blocks a game and took his team all the way to the state championship and a 30-1 record, beating Indiana-bound All-American Alan Henderson in the title game and topping him for Indiana’s Mr. Basketball. It was rare enough to bring Mr. Basketball back to bombed-out Gary, and rarer still to beat out a future Hoosier. But Robinson was a deserving choice: a McDonald’s All-American and the subject of a fierce recruiting battle between Indiana and Purdue, those forever bitter in-state rivals.

But if Robinson had everything he needed in basketball and heart to excel at the collegiate level, what he did not have was the grades to be eligible. So while counterparts like Michigan’s Chris Webber, Henderson, Jason Kidd and other top freshmen made waves across college hoops as one of the best incoming classes in NCAA history, the man who would be known as ‘Big Dog’ was resigned to being simply ‘Big Guy in Street Clothes.’

Without basketball, Robinson struggled with life away from home. He admitted he ate too much and felt depressed without the game he had mastered. But as he often did, Robinson bore down and began to see his missed season as a chance to develop his game and to acclimate to the college experience. To stay focused, Robinson worked the summer before school as a welder back in Gary. He also shunned all media requests that Prop 48 year.

“I figured I wasn’t playing,” he told Sports Illustrated later, “so what was there to talk about?”

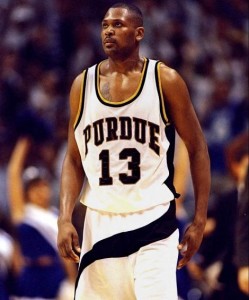

Purdue struggled without him, understandably. But once eligible, Robinson wasted no time. In his much anticipated debut, Robinson dropped a cool 30 in an upset over 16th ranked Connecticut. Just three games into his career Big Dog was averaging 26.7 points and 9.3 rebounds per game with two MVP trophies. More importantly, his team was 3-0.

While the Boilermakers worked to build a team around their star, progress was slow. Purdue managed an 18-win campaign in 1993-94, but the scintillating sophomore season of Robinson closed with a bitter first-round loss to Rhode Island and immediately speculation began that the über-talented Robinson — named second-team All-American and All-Conference – would turn pro, forgoing his junior and senior seasons for the NBA. After all, in that first season at Purdue, Robinson became the first player in 22 years to lead the Big Ten in scoring in his debut go-around, and most around the game were sure he would be an easy top five selection in the 1993 NBA draft, a draft that would feature those other star swing-bigs: Webber, Mashburn, Rogers and Baker.

But Robinson wasn’t ready.

“I felt we didn’t really accomplish anything,” he said then. “I felt last year I wasn’t mature yet. I wasn’t ready to go off into that big world yet. Out there you have to be able to deal with girls, agents, people trying to give you drugs—all that stuff. One morning I’ll wake up and I’ll know it’s time.”

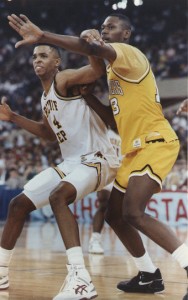

Once he announced his intentions, Robinson and his team got to work, just like he’d always done. The result was a season for the ages for Robinson, and for Purdue. The Boilermakers started the season a school-best 14-0. And with each dominating performance, the accolades for Robinson flowed. Former Knicks coach Stu Jackson, then the head coach at Wisconsin, said, “Glenn Robinson is a joke, he’s so good,” Jackson said. “He’s a man playing among boys, and where he belongs is in the NBA.”

For his part, never one to play coy, Robinson said flatly, “I feel like there’s no one in college that can stop me.”

Robinson would ultimately finish the season with a preposterous 30 points a game scoring average, tops in the nation, to go along with 11 rebounds a contest. He became the first player in Big Ten history to score 1,000 points in a season, finishing with 1,030. More importantly, Purdue was Big Ten champions in 1994. As the Big Ten’s best, Purdue earned a No. 1 seed in the 1994 NCAA tournament. All expected Robinson to shine under the big lights, as he always had, and at first they weren’t disappointed. In a second round win over Alabama, Robinson went for 30 and 11. In the Sweet Sixteen, matched up against Kansas and seven-footer Greg Ostertag, Robinson showed how unstoppable he was, scoring 30 first-half points and throwing down a thunderous dunk right in the big man’s face. Big Dog would finish with 44 points in the 83-78 victory. The win put Purdue coach Gene Keady into the Elite Eight for the first time in his long coaching career. Purdue would next face Duke and its own matchup nightmare, Grant Hill.

Like so many other great scorers, Robinson found that no amount of confidence or heart can overcome that game where it finally isn’t there, where that seemingly endless well of buckets shows itself to actually have a bottom. A combination of a strained back suffered against Kansas and Hill’s All-American defensive prowess proved too much and Robinson scored a season-worst 13 points in the 69-60 loss.

Still, Robinson’s remarkable season ended with a parade of Player of the Year Awards – Naismith, Wooden and AP — in a season that also featured All-American campaigns from such future NBA stars as Kidd, Juwan Howard and Hill. When the awards dinners finally ended, Robinson had to decide whether to come back for one more try or head off to the NBA as the draft’s likely top overall pick. After hemming and hawing and openly discussing a return, Robinson ultimately couldn’t pass up the chance to change his and his family’s fortunes. The Milwaukee Bucks took Robinson No. 1 on June 29, 1994, and after initially pressing for an unthinkable $100 million guaranteed contract, Robinson agreed to $68 million.

No one could have faulted Robinson for his decision. After all, he’d delivered two of the greatest scoring seasons in Big Ten history, as well as carried his team within striking distance of the Final Four. He’d done it without fanfare or bravado. He’d done it with the same blend of tenacity and quiet resolve he’d always had, that steely drive to be the best player on the floor at all times that had made him a star at every level of basketball. NBA GMs raved about the workmanlike attitude Robinson brought to the game. The famed Lakers GM Jerry West said the Big Dog “plays basketball the old-fashioned way,” a high compliment from one of the greatest to ever lace them up.

But in a strange way, basketball brilliance wasn’t something Robinson actively tried to do so much as it was just something he was, something he’d just always been since he was a young man. It was the same thing all the great ones have, that limitless ability to perform at the highest level, buoyed by the kind of deep commitment and tinsel-strength will he’d learned back home, in Gary, where an unwed teen mother had turned Glenn Robinson, the shy kid, into the Big Dog, college basketball’s brightest star.