Past Imperfect: Chris Jackson and the Fallacy of Normal

Posted by JWeill on March 3rd, 2011Past Imperfect is a series focusing on the history of the game. Every Thursday, RTC contributor JL Weill (@AgonicaBoss | Email) highlights some piece of historical arcana that may (or may not) be relevant to today’s college basketball landscape. This week: reliving LSU’s phenomenal Chris Jackson.

How often do you think about what’s normal in your life? Do you ever have to stop and define just what normal is or is normal the very essence of not having to define it? Is it what comes naturally, just something you do without thinking about it? Normal, for most people, is … just what is.

Culturally, we tend to make noise about the things that are not normal – on our best days, that which is better than normal; on our worst, laughing at what passes for normal for others. It’s understandable, really. Who bothers to take note of something that everyone sees as mundane, common, ordinary?

But what about those folks for whom normal is different? For those folks to whom it means not being able to do those mundane things that other people do without thinking. Or maybe it means, in certain cases, people who do things in their own way, with their own quirks, and do them fabulously.

Chris Jackson could do anything he wanted in basketball, only better than the ordinary. When you’re like Jackson, normal just isn’t part of the plan. It’s not even on the blueprints. For Jackson, normal was impossible, at least by the standards the rest of us consider, well, normal. Because no one who looks like and is Chris Jackson should have been able to do the things he could do. To this day, no one has done the things he’s already done.

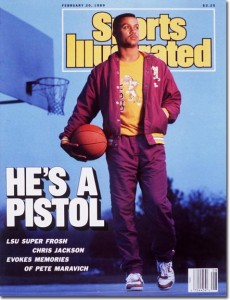

But it’s not as if no one knew what he was capable of, at least in the abstract. Jackson was, after all, a two-time Mississippi High School Player of the Year, and a McDonald’s All-American, at Gulfport High. He was the jewel of legendary Louisiana State coach Dale Brown’s 1988 recruiting class. But it’s unlikely anyone, not even Brown and probably not anyone outside of Jackson himself, thought that a 6’1 string bean like Jackson was capable of dominating a college basketball game like he did for two years. If you’re just learning about it now, watching grainy clips on Youtube, it seems comical, video game-like. If you were around then to witness it, you didn’t believe it even as it was happening. The whole thing seemed, well, abnormal. Super-normal. Extra-ordinary.

Jackson arrived at LSU in the fall of 1988 a kid of circumstances. In a poor town, Jackson was raised by his single mom. Jackson never knew his father. He spent hours and hours at local courts, shooting and shooting until the shot felt perfect off his hand, off his fingertips. He practiced free throws until he didn’t miss them. He once made 283 in a row in high school. But it wasn’t just some sort of overcharged work ethic at play. Jackson was afflicted with Tourette’s syndrome, a neuropsychiatric disorder that causes tics, grunts and uncontrollable spasms and outbursts in those who possess it.

It can, and certainly did in Jackson, also manifest itself as an obsessive perfectionism, effectively convincing the brain that the afflicted cannot stop until perfection has been achieved. This means he cannot stop for exhaustion, cannot stop for dehydration, cannot stop for anything. So what made Jackson lie in bed at night shedding tears of frustration was also what helped make him into an unstoppable offensive force. It wasn’t until 1987, on the cusp of graduating to LSU, that Jackson finally got diagnosed with and got treatment for Tourette’s. Before that? He was just the weird kid that made the crazy noises and movements. He was just the kid down the street who was not normal.

Still, despite his remarkable abilities, as a small and reedy combo guard, few could have imagined how devastatingly good Jackson would be. He had always been able to score, and to shoot – thanks to natural talent and, yes, that neuro-perfectionism. But somehow, without appearing to exert much extra effort, Jackson showed up as ready for college basketball as anyone had ever been as a freshman. More ready, even. In his third game as a collegian, Jackson posted 48 points. In his fifth? 53. How about an NCAA freshman record 55 against Ole Miss? To this day, no one has ever scored more points as a freshman than Chris Jackson did in 1988-89. Not Kenny Anderson, not Jay Williams, not Kevin Durant and not John Wall. No one.

Jackson’s was a star rising, and quickly. Brown thought LSU could be big time behind Jackson and his future star big men Shaquille O’Neal and Stanley Roberts. Brown had scheduled accordingly, even managing to stuff 54,321 – a record at the time for a regular-season college game — into the Superdome to watch Jackson pour in 26 points and upset Alonzo Mourning and mighty Georgetown.

The mighty mite, surrounded by senior Ricky Blanton and then more or less nothing else that first year, took LSU to the top of the SEC for a portion of the season before reality set in on the Tigers, as it often did with Dale Brown’s teams. But reality never really hit Jackson, who just continued his brilliance, finishing with a 30 points per game average, tops in America. Tops in college for a freshman. Ever.

-

Most impressively, Jackson was a little man playing a big man’s game, but with a big man’s heart inside his little man’s body. He was Iverson before Iverson. He was Jimmer Fredette times 10, and Kemba Walker times 20. Jackson could dunk easily at (a listed) 6’1, shoot effortlessly from 27 feet, pass with one hand through traffic and all without changing gears. Even watching it live wasn’t enough to truly grasp it. It just didn’t seem normal for someone to be that good.

Georgetown’s Mourning saw it first-hand: “I never knew which way Chris was going. He puts you in a triple-threat position. You don’t know whether he’s pulling up to shoot or to pass, or whether he’ll keep driving inside or what. Then, which side? Where? He’s everywhere. Give him one step and it’s over. And I think he’s the best shooter in the country.”

That’s how you felt watching Jackson: unsettled, ill at ease, jittery. Fitting, maybe, since that was somewhat how Jackson himself felt most of the time with Tourette’s. While his playing demeanor on the court was placid, nearly emotionless, his facial mannerisms and vocal tics betrayed the synapses firing within him. His face twitched, he blurted out sounds. Some referees didn’t understand. Reporters didn’t understand. It was just so weird.

Despite his historic accomplishments that season, Jackson alone wasn’t enough. He hoisted 32 shots in a loss to Tim Hardaway and UTEP in the first round of the NCAAs, another in a series of underachieving squads under Brown. Still, ignoring the finish, it was impossible to ignore what Jackson had done. And folks didn’t. He was a consensus first-team All-American and the SEC Player of the Year. There was no one else to compare him to.

In many ways, Jackson had caught everyone napping. And the sheer volume Jackson produced almost didn’t happen. Because most of the other heralded members of Jackson’s ’88 recruiting class were eligibility casualties, Brown had to let Jackson roll. Imagine bottling up the best drink you can imagine then only allowing folks a thimbleful at a time. The world wanted, and got, huge gulps of Chris Jackson. LSU under Brown had been a good program, but a streaky one. When no one expected much, the Tigers made waves. When they were supposed to be good, they flopped. It was the curse of the Tigers. But Brown could recruit, and he set out to build a team that couldn’t lose. Brown infused the program with immense talent in those years. With O’Neal, Roberts and the other stars arriving, and with the extraordinary Jackson, there was no reason LSU shouldn’t dominate the SEC and the rest of the NCAA. They were ranked No. 2 in the preseason. And yet, it didn’t happen. LSU struggled to maintain any cohesiveness and consistency. Was it too many stars? Was it Brown over-coaching? Or was Jackson the kind of player, people started to whisper, who simply couldn’t share the ball?

There were times when the Tigers looked like the best team in America. Like when, led by Jackson’s 35 points, LSU beat UNLV by two, 107-105, the same UNLV team that would go on to win the national title in a romp over Duke. Or how about when Jackson dropped 49 including 10 three-pointers in a win at Tennessee? Electric stuff. Still, the head-scratching losses continued. A decimated Kentucky program, reeling from NCAA sanctions and personnel losses, faced LSU late in the season. Kentucky had no business beating LSU. Jackson scored 41. And still, LSU lost.

Jackson had another All-American season, finishing No. 2 in scoring behind a kid out West named Hank Gathers. But even talented teammates couldn’t get LSU and Jackson over the hump. After all those points, after all that brilliance, all the times he put the team on his back, it wasn’t the rest of them that faltered this time. Amazingly, it was Jackson. Saddled by a chest cold, the best collegiate backcourt scorer most folks would ever see finished his last college game with only 13 points. That Jackson’s career would end so unceremoniously, in a second-round defeat to another amazing guard, Kenny Anderson, leading a Georgia Tech team on the way to the Final Four, was puzzling. It wasn’t the way it was supposed to be.

Not long after the end of his sophomore season, Jackson announced he’s go to the NBA. Few expected much to change at the next level. Jackson was too good. But he fell out of shape, and the coach of the team that drafted him, Paul Westhead of the Denver Nuggets, either didn’t get him or didn’t play someone he didn’t think would help him win. But Denver wasn’t winning.

Lacking confidence, trying to lose weight and battling ankle injuries — and fighting with the Tourette’s he’d always struggled with, too — Jackson finally found peace. First, in religion and later, in basketball. Always a man of faith, now Jackson found himself in Islam. Islam required dedication, a pursuit of perfection. It required focus and discipline and an almost obsessive devotion to Allah. Islam began to change the way Jackson felt. Basketball came back to him. he would be the NBA’s Most Improved Player in 1993. He led the Nuggets in scoring. He nearly broke the record for free throw shooting. Islam had changed Jackson, and it had changed his life. So he changed his name – to Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf. To most people, that sounded weird. Who does that? Especially when you’re a famous basketball star? Normal people don’t do something like that.

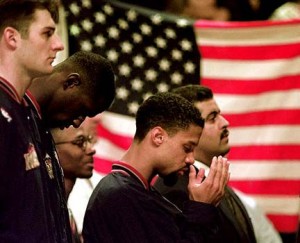

But normal people don’t know what it is to be Chris Jackson, or Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf. So when, during the 1996 season, Abdul-Rauf refused to stand for the national anthem out of protest, folks went crazy. The league went crazy, suspending him. Never mind that there is no law against sitting during the anthem, nor that anyone has a right not to. Never mind that Abdul-Rauf’s reasoning was about protesting what he felt were injustices. Never mind. It was just weird, the wrong thing to do. That’s what normal, average America thought.

But Jackson/Abdul-Rauf didn’t back down. With the same level of certitude he’d always played basketball with, with that same sense that the next shot was going to go in the basket, Abdul-Rauf went on with his life. He and the league worked out a compromise whereby Abdul-Rauf would pray during the anthem, but stand with his teammates. But the stigma of the incident seemed to follow Abdul-Rauf. Two years after the anthem incident, Abdul-Rauf left the NBA for Turkey. But finding basketball life there less than acceptable, he retired from basketball. Abdul-Rauf then went on to found an Islamic congregation and become an imam back home in Mississippi. It’s the kind of thing you’d never expect to happen, but it did.

And this month when he turns 42, he’ll continue to suit up for Kyoto Hannaryz, in a Japanese league, having come out of retirement for the third time three years ago. This season, he’s averaging around 15 points and shooting almost 90% from the foul line. Playing professional basketball at 42 seems a little weird, right? Just something no normal person would do. Or could do.

Exactly.

Enjoyed reading this piece about Abdul-Rauf. While I didn’t experience his special college days and only started following his NBA carreer, he definitely is legend. That is why I will soon attend one of his games in Japan as I absolutely want to see him play the game.